AIMS Journal, 2021, Vol 33, No 4

To read or download this Journal in a magazine format on ISSUU, please click here.

By the AIMS Campaigns Team

The National Maternity and Perinatal Audit (NMPA) is a group led by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) and including the Royal College of Midwives (RCM), the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM). AIMS is represented on the NMPA’s Clinical Reference Group, which provides us with an opportunity to comment on reports at a draft stage.

The NMPA is commissioned by the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP) as part of the National Clinical Audit and Patient Outcomes Programme (NCAPOP), on behalf of NHS England, the Welsh Government and the Health Department of the Scottish Government, to carry out audits of the maternity services in England, Wales and Scotland, using data collected from hospitals. In addition to ongoing clinical audits and organisational surveys, this work includes carrying out ‘sprint audits’ looking at particular aspects of maternity care. The main purpose of these is to explore the feasibility of adding further categories of clinical data to the regular audits, but they can also throw valuable light on the experience of particular groups of maternity service users.

A strength of these sprint audits is the involvement of a lay advisory group, in this case made up of members who had themselves experienced pregnancy with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or more. For example, they were consulted on the language to be used, which led to the decision to refer to groups by their BMI[1] thresholds rather than using terms such as ‘obese’ or ‘high BMI’. The group also recommended outcome measures they thought were important to include, made some very insightful comments on the interpretation of the findings, and reviewed the draft of the key findings and recommendations.

The audit (NMPA BMI Over 30 Report.pdf[2]) reviewed the available data on births in the two years from 1 April 2015 to 31 March 2017 in England, Wales and Scotland. The audit provides “a unique opportunity to describe the diversity of the women who gave birth during the audit period, including how their characteristics differ by category of BMI”. Its main purpose was to compare rates of intervention and outcomes for those with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or above in pregnancy to the rates for those with a BMI in the range 18.5–24.9 kg/m2. In doing so, the audit team sought to determine the characteristics of women in these two BMI categories; to determine where they give birth; and to “explore the feasibility of reporting NMPA outcome measures for women and their babies, according to BMI category, parity and maternal risk status at birth.” The measures used are ones previously developed by the NMPA for their clinical audits.

A report such as this has limitations; while it can tell us what pregnant women and people with a higher BMI have experienced, it has limited ability to identify why this was the case. It is helpful that the authors have identified a number of areas where better data or more research is needed. For example, several measures requested by the lay advisory group unfortunately could not be analysed due to lack of sufficient data. These included access to birth in water, monitoring of fetal growth by ultrasound, access to perinatal mental health services and prevention of venous thromboembolism. Hopefully, the report’s recommendations to record and report this data will enable these important measures to be looked at in future.

The report presents the measures for three categories: mothers who had not birthed before (nulliparous); those who had birthed before (multiparous[3]) and only had vaginal births, and those who had birthed before and had at least one caesarean. This proved to be very helpful in demonstrating how the risks of interventions and of undesirable outcomes are not the same for everyone with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or above, as described below. This illustrates the need for personalised care rather than blanket recommendations based on BMI alone.

The importance of this report’s focus is underlined by the fact that over 20% of those in the sample for whom the BMI was recorded fell into the category of BMI of 30 kg/m2 or above. Recommendations or guidelines based on BMI therefore have the potential to affect the birth experiences of huge numbers of pregnant women and people.

The audit comments on the ethnic make-up of the different BMI groups. There was a higher proportion of women categorised as “of South Asian ethnicity” in both the group with a BMI under 18.5 kg/m2 and that with a BMI between 30 and 34.9 kg/m2. Those with BMI of 35 kg/m2 or above were more likely to be of white or Black ethnicity. Unfortunately, there is no analysis of how ethnicity and BMI might interact to affect maternity outcomes, but hopefully the forthcoming sprint audit on Ethnic and Socio-economic Inequalities will shed some light on this.

It is probably no surprise that the chances of experiencing a medical procedure such as induction or unplanned caesarean, or a serious birth-related health problem for mother or baby, were found to increase with increasing BMI. However, as the report makes clear “[w]e do not know whether this is because women with higher BMI are more likely to develop complications requiring intervention or because of differences in the clinicians’ threshold to intervene.” In other words, is labelling someone with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or above as ‘high risk’ a self-fulfilling prophecy, at least in some cases? As one of the lay group (Mari), quoted in the report, commented:

“There’s a tendency in obstetric circles to [assume that] all emergency caesareans must have been necessary, all inductions must have been necessary, and not acknowledge that actually the previous care can be that conveyor belt of interventions that ends up in that, whether that’s repeated scans, or whether that’s going through an induction process, leading to a caesarean.”

The audit identified that a number of risk factors, including diabetes and high blood pressure, were increasingly common as BMI increased. Also, those living in the most deprived areas were more likely to either have a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or above, or one under 18.5 kg/m2. It is probable that the association of these risk factors with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or above is at least part – and perhaps a major part – of the reason for more interventions or birth-related problems occurring with this level of BMI.

It is also important to remember that being ‘at higher risk’ does not mean that a problem is inevitable. The report comments that though “[w]omen with BMI of 30 kg/m2 or above have at least a two-fold higher risk of complications” (such as gestational diabetes and caesarean birth) compared to women with a BMI in the ‘healthy range’ (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), “approximately one-third of these women have a pregnancy and birth without complication.”

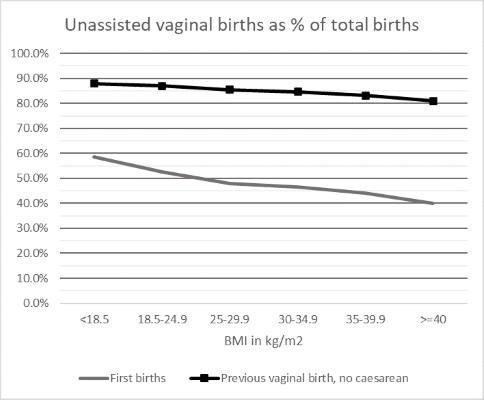

One telling finding - illustrated in the chart below - was that for the group who had previously given birth vaginally but never had a caesarean, a higher BMI only marginally reduced the chance of having an unassisted (by which they mean a vaginal birth without the assistance of forceps or ventouse) vaginal birth next time. At least 80% of those in this group who had a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or above had an unassisted vaginal birth, compared with just under 90% of those with a BMI between 18.5 and 24.9 kg/m2. Treating a person who has birthed before and not had a caesarean as ‘high risk’ purely because of their BMI therefore seems illogical.

For those giving birth for the first time, the chances of an unassisted vaginal birth dropped more steeply with increasing BMI. However, even with a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or above, 40% experienced this, compared with just over 50% of those with a BMI between 18.5 and 24.9 kg/m2.

Another interesting measure is “birth without intervention”. NMPA uses two definitions for this: definition 1 reports birth with spontaneous onset and progression and spontaneous birth, without epidural and without episiotomy; definition 2 omits spontaneous progression. The proportion of births meeting these definitions declined with increasing BMI for all three groups. However, “approximately one in five women with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or above have a birth without intervention”. For those with previous vaginal births but no caesareans, the figure was 50% for those with a BMI of 30 – 34.9 kg/m2. The lay group “hoped that this finding may be used to support clinicians to offer birth in alongside midwifery units (AMUs) to more women with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or above” – a hope which AIMS shares.

The AIMS Helpline frequently hears from women who are being refused support for a homebirth or admission to a Birthing Centre purely because of their BMI, so it is not surprising that the audit found a decrease in the proportion of births taking place in these settings with increasing BMI, as this chart shows. However, it is worth noting that some people were supported to use a Freestanding Midwifery Unit, even in the group with a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or above.

Given that interventions are typically lower for births outside hospital than in an Obstetric Unit this could be another factor affecting the increase in intervention rates with increasing BMI. Unfortunately, the data does not distinguish birth in an Alongside Midwifery Unit from those in an Obstetric Unit. It also only records where the birth took place, not where the labour started, so we cannot tell what transfer rates were like.

The report comments that for women with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or above but no other risk factors “births without complication or intervention are more likely and they may therefore be suited to giving birth in midwifery-led birthing centres, particularly if they have previously given birth vaginally.” AIMS hopes that all NHS Trusts/Boards will recognise this and amend their guidelines for Birth Centre admission accordingly. Similarly, we feel that the fact that someone has a higher BMI should not be put forward as an argument against planning a homebirth.

The rate of planned (elective) caesareans appears to be little affected by BMI for first births or births after a previous vaginal birth but no caesarean, remaining under 10% for all BMI ranges. Repeat planned caesareans are more common with increasing BMI, but how many are at the mother’s request and how many at the consultant’s urging we do not know.

Unplanned (emergency) caesareans increase with BMI, especially in the case of first births, but much less so for those who have birthed vaginally before. For this group they did not rise above 10% of all births even with a BMI over 40 kg/m2.

The proportion of women who planned a VBAC and the proportion who achieved a vaginal birth both declined with increasing BMI. However, 50% of those with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or above who planned a VBAC were successful, compared with around 65% of those with a BMI of range 18.5–24.9 kg/m2. A higher BMI is clearly not a barrier to a successful VBAC or a reason not to plan one.

The chances of a stillbirth, a premature birth or a baby with a birthweight in the top 10% of the population (called large for gestational age or LGA), though still uncommon, do increase somewhat with increasing BMI. The stillbirth rate for mothers with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or above was six in one thousand births, compared to three in one thousand for those with a BMI of range 18.5–24.9 kg/m2. It is not known why this is, and the report calls for more research to investigate and explore whether it is possible to identify which babies are at risk.

The report points out that the higher chance of having an LGA baby may be linked to the higher rates of diabetes and gestational diabetes in mothers with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or above.

Babies born to mothers with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or above were found to be more likely to be judged in poor condition at birth (with an APGAR score under 7/10). However, the increase was small and rates still low – no more than 2% for the highest BMI groups. Similarly, there was an increase in the proportion of babies admitted to a neonatal unit (from around 6% to around 10%) or needing mechanical ventilation (from around 0.5% to around 1%) with increasing BMI. The increase was more marked for first births.

As with the increase in interventions, we do not know the reason for the higher level of health problems in babies with increasing maternal BMI. The authors comment that “[g]iven that women with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or above are more likely to be from the most deprived areas, with different distributions of ethnicity and higher prevalence of comorbidities, these characteristics may contribute to some of the differences seen” in outcomes for their babies. They also speculate on the impact of difficulties in monitoring the well-being of babies if the mother has a higher BMI, and that the higher number of LGA babies could lead to more cases of shoulder dystocia[4]. However, there is a lack of evidence on the risks and benefits of offering induction at term for LGA babies of mothers with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or above.

Babies born to mothers with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or above were also less likely to have skin-to-skin contact in the first hour after birth, or to have breastmilk as their first feed. The lay advisory group commented that this was likely to be due to a lack of individualised support, and they could see no good reason for skin-to-skin contact being less common. The report calls for all women (regardless of BMI) and their babies to be supported to experience skin-to-skin contact within an hour of birth and for all women to be offered breastfeeding information and support during pregnancy and again shortly after the birth. It is worrying that this needs to be a recommendation! However, given that it appears to be so, AIMS hopes that all maternity services will take note that “[w]omen with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or above may require support to be tailored to their specific needs and to be provided by a healthcare professional who is trained to adapt breastfeeding techniques for women with a higher BMI.” With one in five mothers falling into this category, the need for tailored support and training for staff is clear.

The audit explored whether it would be feasible for future audits to categorise “maternal and neonatal outcomes according to maternal parity and risk status at the time of admission for birth.” This was in recognition of the fact that “women with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or above are not equal in terms of their risk of receiving interventions or experiencing adverse outcomes. Women vary in terms of their BMI category and parity, but also by their past obstetric history, antenatal complications and medical comorbidities, as well as in their values and choices.” Although AIMS was pleased to see this recognition by the NMPA, we would hope that midwives and doctors would consider all these individual factors in drawing up a personalised care plan, rather than the BMI alone.

This section of the report looked at selected outcomes for five categories (using data for England only):

The level of risk was assessed using the criteria in the NICE guideline Intrapartum care for healthy women and babies.[5] They decided not to split the fifth group into high and low risk “because a previous caesarean birth itself is a significant risk factor.” This seems like a missed opportunity to consider potential differences within this group.

The findings were similar to those in the main report, but it was clear that outcomes at a given level of BMI tended to be better for those categorised as ‘low risk’, especially in the case of those giving birth for the first time.

Dividing pregnant women and people into low and high risk groups in this way may help a little in encouraging midwives and doctors to tailor care to their needs, compared with the attitude that considers all those with a higher BMI to be ‘high risk’. However, truly personalised care that looks at the whole person, their circumstances, needs and wishes, would be so much better.

[1] Editor’s note: For those new to the concept of BMI, and to BMI as a measure of health risk, the following articles explain what it is and why it is a controversial measure of health:

Fogoros R N (2021) Is Being a Little Overweight Really OK? Resolving the controversy over BMI measurements. www.verywellhealth.com/is-being-a-little-overweight-ok-bmi-controversy-1746304

Humphreys S. (2010) The unethical use of BMI in contemporary general practice. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2930234

[2] NPEU (2021) National Maternity and Perinatal Audit NHS - Maternity Care for Women with a Body Mass Index of 30 kg/m2 or Above https://maternityaudit.org.uk/FilesUploaded/NMPA%20BMI%20Over%2030%20Report.pdf

[3] Editor’s note: In some definitions, multiparous is defined as having given birth (after 24 weeks) more than once prior to the current pregnancy and primiparous is defined as a woman who has given birth (after 24 weeks) only once before the current pregnancy. In the NMPA report, women who have only given birth after 24 weeks only once before are included under the multiparous definition. https://patient.info/doctor/gravidity-and-parity-definitions-and-their-implications-in-risk-assessment

[4]RCOG (2013) Information for you: Shoulder dystocia. www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/patients/patient-information-leaflets/pregnancy/pi-shoulder-dystocia.pdf

[5] NICE (2014) Intrapartum care for healthy women and babies. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg190 (updated 2017)

The AIMS Journal spearheads discussions about change and development in the maternity services..

AIMS Journal articles on the website go back to 1960, offering an important historical record of maternity issues over the past 60 years. Please check the date of the article because the situation that it discusses may have changed since it was published. We are also very aware that the language used in many articles may not be the language that AIMS would use today.

To contact the editors, please email: journal@aims.org.uk

We make the AIMS Journal freely available so that as many people as possible can benefit from the articles. If you found this article interesting please consider supporting us by becoming an AIMS member or making a donation. We are a small charity that accepts no commercial sponsorship, in order to preserve our reputation for providing impartial, evidence-based information.

AIMS supports all maternity service users to navigate the system as it exists, and campaigns for a system which truly meets the needs of all.