To read or download this Journal in a magazine format on ISSUU, please click here

AIMS Journal, 2019, Vol 31, No 1

By Debbie Chippington Derrick and Nadia Higson

It is very common for women to be told they need to have their labour induced before 42 weeks because otherwise they are at increased risk of stillbirth. Here we look to see if the evidence actually supports this belief.

There are different types of evidence that might help us answer this question, but unfortunately this evidence is contradictory, and there has been much contention about whether induction of labour should be offered to women purely on the basis of longer pregnancy. Term birth is defined as a birth that occurs anywhere between 37 and 42 weeks of pregnancy, with births after 42 weeks being classed as ‘post-term’. However, induction of labour at some point after 40 weeks of pregnancy has been routinely carried out by some in obstetrics since the 1970s.

Definitions used in this article‘Stillbirths’ refers to deaths which occur before birth. It can be sub-divided into antepartum stillbirths (those which occur before the start of labour) and intrapartum stillbirths (which are where a baby was alive at the start of labour but shows no signs of life at birth and cannot be resuscitated). ‘Neonatal deaths’ are where babies who were born alive die in the first week of life. ‘Perinatal deaths’ are the total of all stillbirths and neonatal deaths. It is normal to give rates of stillbirths and perinatal deaths as deaths per 1000 births, whilst neonatal deaths are given as per 1000 live births. |

What do the guidelines say?

The NICE Guidelines on Induction of labour1 and the update2 both recommend that induction is offered between 41 and 42 weeks of pregnancy, stating that there appears to be a reduction in perinatal deaths with induction of labour at this point, compared with waiting beyond 42 weeks. The NICE update mainly bases this on the Cochrane review3. There has since been another Cochrane review4 which has the same conclusion and we can expect to see the NICE guidelines which will be published in July 2020 to repeat this information and the recommendation for induction purely on the basis of longer gestation. However, these reviews do acknowledge that the risk of stillbirth appears to be very low in longer pregnancies and the latest one suggests it would be necessary to induce 426 women around 41 to 42 weeks to avoid one stillbirth.

The Cochrane reviews are what is called a meta-analysis which combine the data from a number of research trials. One problem with this type of review is that the results can vary depending which trials the authors choose to include. Other reviews which have addressed the same question have reached different conclusions. For example, one which looked only at studies of induction at 41 weeks or beyond found no evidence that this was beneficial5. Another, which included only trials published since 1990 found no significant difference in perinatal mortality whether labour was induced before 42 weeks or not6.

Another type of information comes from population studies, which looked back at the records of outcomes for mothers who gave birth at different gestations. Although it’s true that some of these have shown a rise after 40 weeks in stillbirth rates7 or perinatal death rates8 (which includes stillbirths and deaths in the first week of life), the risk remains low, and is no greater at 42+ weeks than it was at 37 weeks. The two graphs below show the data from these studies.

UK Confidential Enquiries

Most years since 2005 the UK confidential enquiries have reported on the data collected from the 20,000 or so women whose pregnancies have continued to week 42 or beyond and these mothers have provided us with a more recent UK based population study. This current article is based on an update of the detailed analysis of this data previously published by Margaret Jowitt9.

What the confidential enquiries enable us to do is to look at how the outcomes of post term pregnancies compare with the outcomes of pregnancies where birth took place between 37and 42 weeks. The last 10 Confidential Enquiry reports, from between 2004 and 2016, have consistently shown that the risk of stillbirth and neonatal death is lower for mothers who birth beyond 42 weeks than it is for all those who birth at term.

The UK has made concerted efforts to bring down the perinatal mortality rate since 1991 when the Confidential Enquiries into Death and Stillbirth in Infancy (CESDI) was set up, and rates have steadily declined. These Confidential Enquiries look at some cases in greater detail to try and also try to tease out common factors in stillbirths and neonatal deaths. They look at factors like maternal age, ethnicity, birth weight and length of gestation. CESDI reporting was combined with Confidential Enquires into Maternal Death to become CEMACH in 2003 and from 2008 was renamed CMACE and run by the RCOG. In 2012 the contract for the work went to the National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit in Oxford and was renamed Mothers and Babies, Reducing Risk through Confidential Enquiries (MBRRACE-UK), leading to a gap in reporting, and therefore no reports for 2010 and 2012.

The Confidential Enquiries provide data for the whole of the UK giving numbers of stillbirths, (which since the reports in 2014 have been broken down into antepartum stillbirths and intrapartum stillbirths) and of neonatal deaths.

Induction of labour at some point before 42 weeks of pregnancy is being offered in an attempt to prevent antepartum stillbirth. In situations where this happens, no one, parents or health care providers can avoid the feeling that if only labour had been induced earlier, these babies might have lived. Antepartum stillbirths outnumber intrapartum stillbirths by a factor of 10:1 and so it is thought that the greatest scope for reducing the stillbirth rate is by inducing labour earlier. Whilst this may appear logical, we need to consider whether this recommendation is supported by the evidence. Women are often put under pressure to accept induction particularly at 41 weeks and certainly as they approach 42 weeks. Induction, however, is not without risk for both mother and baby4,10.

Even when trials are pooled in a meta-analysis such as the Cochrane review mentioned above, the numbers of births included in these studies are still very small compared to whole population statistics. In contrast, the huge numbers of births included in the data collected by MBRRACE-UK and its predecessors can help to give a clearer picture of the issue. While these statistics cannot provide an answer to the question as to whether induction protects against stillbirth, they do provide clear information about how many stillbirths and neonatal deaths occur in pregnancies in the UK which continue beyond 42 weeks, and give a comparison with the rates for preterm births (before 37 weeks) and at term (between 37 weeks to 41 weeks + 6 days).

The following table provides the data from the reports between 2004 and 2016. The data collected and how it is presented has changed over the years. For example, in some years, details for each week of gestation were given, whilst other reports gathered together the data for several weeks. Nevertheless, the data still tells the same story

It can be clearly seen that none of the Confidential Enquiries reports support the statement that the risk of stillbirth increases with advanced gestation, on the contrary, the tables all show that the risk of both stillbirth and neonatal mortality is lowest at 42+ weeks.

|

Report |

Week of Gestation |

Number of Births |

Number of stillbirths |

Stillbirth Rate per 1000 births |

Number of Neonatal deaths |

Neonatal Death Rate per 1000 live births |

|

CEMACH 200411 |

37–41 |

533,800 |

1084 |

2.0 |

481 |

0.9 |

|

|

42+ |

28,300 |

33 |

1.2 |

22 |

0.8 |

|

CEMACH 200512 |

37 |

35,900 |

218 |

6.0 |

79 |

2.2 |

|

|

38 |

87,600 |

238 |

2.7 |

123 |

1.4 |

|

|

39 |

136,900 |

236 |

1.7 |

116 |

0.8 |

|

|

40 |

181,900 |

246 |

1.4 |

123 |

0.7 |

|

|

41 |

121,300 |

214 |

1.8 |

97 |

0.8 |

|

|

42 |

23,300 |

26 |

1.1 |

16 |

0.7 |

|

|

42+ |

4,500 |

3 |

0.7 |

2 |

0.4 |

|

CEMACH 200613 |

37 |

39,533 |

239 |

6.0 |

76 |

1.9 |

|

|

38 |

94,508 |

211 |

2.2 |

108 |

1.1 |

|

|

39 |

151,755 |

236 |

1.6 |

106 |

0.7 |

|

|

40 |

189,435 |

249 |

1.3 |

113 |

0.6 |

|

|

41 |

136,637 |

199 |

1.5 |

79 |

0.6 |

|

|

42+ |

29,342 |

37 |

1.3 |

15 |

0.5 |

|

CEMACH 200714 |

37-41 |

* |

* |

1.9 |

* |

0.9 |

|

|

42+ |

* |

* |

1.1 |

* |

0.7 |

|

CMACE |

37-41 |

* |

1,242 |

1.9 |

526 |

0.8 |

|

|

42+ |

* |

26 |

0.8 |

23 |

0.7 |

|

CMACE |

37-41 |

* | * | * | * |

0.8 |

|

|

42+ |

* |

* |

* |

* |

0.7 |

|

MBRRACE 201317 |

37-41 |

641,682 |

1,095 |

1.7 |

476 |

0.7 |

|

|

42 |

26,504 |

34 |

1.3 |

16 |

0.6 |

|

MBRRACE 201418 |

37-41 |

689,795 |

1,143 |

1.7 |

493 |

0.7 |

|

|

42 |

33,840 |

54 |

1.6 |

20 |

0.6 |

|

MBRRACE 201519 |

37-41 |

* |

1,025 |

1.5 |

500 |

0.7 |

|

|

42 |

* |

15 |

0.8 |

7 |

0.4 |

|

MBRRACE 201620 |

37-41 |

678,093

|

1,031 |

1.5 |

468 |

0.7 |

|

|

42 |

18277 |

19 |

1.0 |

9 |

0.5 |

* Note: this figure was not given in the report

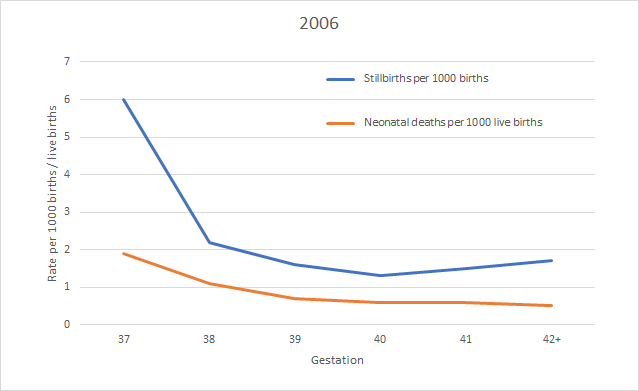

The data for 2005 and 2006 which was given by each week of gestation and these charts show clearly the declining rates for both stillbirth and neonatal death with gestation.

Comparison of rates of term and ‘post term’ stillbirths

So, we have ten years of data which consistently shows that the stillbirth and perinatal mortality rates have been lower for women birthing at 42+ weeks than for those who birthed at 37 - 42 weeks. The numbers of women concerned is huge; around 20,000 women every year take part in the natural experiment of allowing pregnancy to continue until 42 or more weeks.

This data does not include numbers of congenital abnormality, and as some of the stillbirths recorded at all gestations will have been unavoidable because of congenital abnormalities, this information would provide a clearer picture. What is also lacking is classification of stillbirth rates by mode of onset of labour (spontaneous, induction or pre-labour caesarean).

Another set of data, covering England and Wales, comes from the Office for National Statistics ‘Birth Characteristics’ reports. Although it records the same births and deaths, this data comes from birth registrations and “where relevant, birth registrations are linked to their corresponding NHS birth notification to enable analysis of further factors such as gestation of live births”. Therefore the figures are slightly different, but show similar patterns to the findings which were reported by CEMACH, CMACE and MBRRACE. The live birth and stillbirth number by gestational age are available from 2014 to 2017 and the table below shows the rates for gestations of 37 weeks onwards. Again, it can be seen that there is no rapid rise is stillbirth rates beyond 40 weeks.

|

Source21 |

Gestational age at birth (weeks) |

All Births |

Stillbirths |

Stillbirth rate per 1000 births |

|

ONS 2014 |

37 |

46,701 |

211 |

4.52 |

|

|

38 |

93,000 |

221 |

2.38 |

|

|

39 |

167,487 |

201 |

1.20 |

|

|

40 |

184,930 |

215 |

1.16 |

|

|

41 |

127,334 |

175 |

1.37 |

|

|

42+ |

20,729 |

29 |

1.40 |

|

ONS 2015 |

37 |

50,124 |

194 |

3.87 |

|

|

38 |

94,161 |

199 |

2.11 |

|

|

39 |

172,011 |

200 |

1.16 |

|

|

40 |

184,788 |

212 |

1.15 |

|

|

41 |

121,403 |

123 |

1.01 |

|

|

42+ |

18,415 |

12 |

0.65 |

|

ONS 2016 |

37 |

53,532 |

190 |

3.55 |

|

|

38 |

97,157 |

214 |

2.20 |

|

|

39 |

175,683 |

161 |

0.92 |

|

|

40 |

181,029 |

225 |

1.24 |

|

|

41 |

115,103 |

119 |

1.03 |

|

|

42+ |

17,747 |

21 |

1.18 |

|

ONS 2017 |

37 |

56,003 |

162 |

2.89 |

|

|

38 |

97,924 |

198 |

2.02 |

|

|

39 |

175,057 |

146 |

0.83 |

|

|

40 |

173,379 |

178 |

1.03 |

|

|

41 |

105,743 |

109 |

1.03 |

|

|

42+ |

15,700 |

15 |

0.96 |

Currently, women are being led to believe that there is a high chance that their baby will die if they continue with their pregnancy beyond 42 weeks. However, even those studies which appear to show a protective effect of induction before 42 weeks make it clear that the risks of continuing pregnancy beyond this point are extremely low; and the evidence presented in this article does not shows that women who are making the decision to continue their pregnancy beyond 42 weeks are encountering increased risk of stillbirth. It also shows that the rate of perinatal mortality is lowest at 42+ weeks.

Health care providers need to understand what this data shows and share it with women to allow them to make informed decisions about whether, or not, to accept induction.

We appeal to MBRRACE to reinstate the reporting by week of gestation instead of grouping the data as they have done in recent reports. We also call on the NICE Induction Guideline Development Group to consider and report on this data, and hope to see this included when the document comes out for consultation before its publication in July 2020.

The AIMS Journal spearheads discussions about change and development in the maternity services..

AIMS Journal articles on the website go back to 1960, offering an important historical record of maternity issues over the past 60 years. Please check the date of the article because the situation that it discusses may have changed since it was published. We are also very aware that the language used in many articles may not be the language that AIMS would use today.

To contact the editors, please email: journal@aims.org.uk

We make the AIMS Journal freely available so that as many people as possible can benefit from the articles. If you found this article interesting please consider supporting us by becoming an AIMS member or making a donation. We are a small charity that accepts no commercial sponsorship, in order to preserve our reputation for providing impartial, evidence-based information.

AIMS supports all maternity service users to navigate the system as it exists, and campaigns for a system which truly meets the needs of all.