AIMS Journal, 2021, Vol 33, No 3

To read or download this Journal in a magazine format on ISSUU, please click here.

By Megan Disley

On the 14th January 2021, the latest MBRRACE-UK report was released[1]. This annual report from the Maternal, Newborn and Infant Clinical Outcome review programme looks at data from the UK and Ireland confidential enquiries into how many women had died during childbirth, and the 12 months after, for the three years 2016 to 2018. The report provides statistics on these deaths as well as summaries on the circumstances around them; and makes suggestions on prevention and lessons to be learnt. The report can be read in full[2], or an infographic is available[3]

Important findings from the 2020 MBRRACE report include:

What does the report say?

It is important to remember that pregnancy in the UK remains very safe. In the UK, 2,235,159 women gave birth during the three-year period from 2016-2018. Of these, 566 died from either direct causes (deaths related to obstetric complications during pregnancy and up to 12 months after birth) or indirect causes (deaths associated with a disorder which is exacerbated by pregnancy) during and up to the first year after pregnancy. 217 of these deaths occurred within pregnancy or up to six weeks after giving birth[4].

Cardiac disease remains the leading cause of indirect maternal death in the UK. Epilepsy and stroke together are the second most common indirect cause, and third commonest cause of death overall, due to the statistically significant increase in Sudden Unexpected death in Epilepsy (SUDEP)[5]. This refers to deaths in pregnant women with epilepsy that are not caused by either injury, drowning, or any other known causes[6]. The exact causes of these deaths are not known and there may not be any one single explanation. The report does go on to detail that, in many incidences, these deaths are related to inadequate medication management for these women either before or during their pregnancy. Due to the doubling in cases of SUDEP, it has become the key focus of this year's report.

Thrombosis and thromboembolism (blood clots) remain the leading cause of direct maternal deaths during or up to six weeks after birth. Maternal suicide sadly remained the leading cause of direct deaths that occurred within a year of pregnancy.

The report states that 90% of the 566 women who died had multiple problems which included both physical and mental health problems. The infographic version and Lay report, talk about a constellation of biases (figure 1) that lead to the maternal deaths. Figure 1 shows how systemic biases due to pregnancy, health and other issues prevented these women with complex and multiple needs from receiving the care that they needed.

Figure 1. Constellation of biases leading to maternal deaths. MBRRACE infographic.

How does this compare to previous years?

Overall, there was a non-significant increase in the overall maternal death rate in the UK between 2016-18 compared to 2013-15.

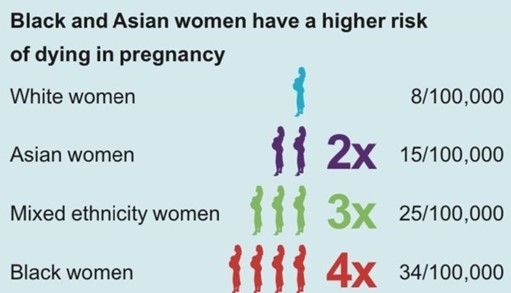

Outcomes for women from different racial groups are not equal. There remains more than a four-fold difference in the mortality rates amongst women from black ethnic backgrounds, a three-fold difference for mixed ethnicity women and almost a two-fold difference in women from Asian ethnic backgrounds compared to white women.

Figure 2. Disparities in maternal deaths in Black, Asian, and Mixed ethnicity women.

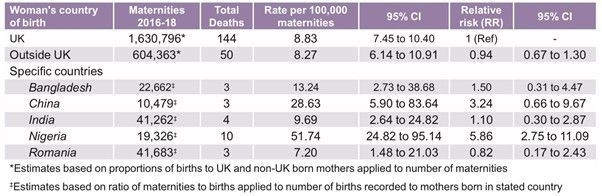

26% of the women who died (in the perinatal period, up to six weeks after the birth) between 2016-18 were born outside of the UK, 36% of whom were not UK citizens. People born in certain countries had a significantly higher risk of death compared to those born in the UK. Table 1 is taken directly from the MBRRACE report which shows the number of deaths from certain countries, those with the highest number of deaths. It is very clear here that the relative risk is higher for those women from specific countries.

Table 1. Maternal mortality rates according to the mother's country of birth (selected countries ) 2016-18.

There remains a difference in mortality rates in different areas and ages. Women living in the most deprived areas are almost three times more likely to die compared to those living in the most affluent areas of the country. 8% of those who died experienced severe and multiple disadvantages, which is an increase of 2% from the last report. The main elements being substance abuse, ill health, and domestic abuse.

20% of women who died were known to social services, a proportion that has increased steadily over time since the 2012-14 report. This further highlights the vulnerability of many people who died.

Let’s talk about SUDEP

As previously stated, epilepsy was a key focus for this year's report. SUDEP occurred nearly twice as often in 2016-18 compared to the previous three years. Most of these women who died had clear risk factors, but did not have risk or prevention methods discussed with them or put in place, or even pre-pregnancy counselling. Some of those who died were either living or sleeping alone. As pregnancy is a known risk factor for SUDEP, it is imperative that strategies are discussed with the pregnant women and people, and their families, and prevention measures are put in place.

Currently, there are no specific recommendations about the discussion of SUDEP and risk minimisation within the RCOG (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists) green-top guideline on epilepsy on pregnancy. The report recognises that this needs to change and there needs to be guidance developed to ensure SUDEP awareness. It recommends that there should be clear standards of care for joint maternity and neurological services which would allow for a simple referral process, and prompt reviews. Other recommendations include all maternity units having access to an epilepsy team, having a maximum referral time of two weeks, and, where necessary, involving social services to ensure that pregnant women and people have safe accommodation arrangements in place.

What has been actioned since the previous report?

On a positive note, conversation has finally now begun to change. It is now recognised that the disparities in maternal mortality just because of a mother or birthing person’s ethnicity is quite simply not acceptable. AIMS is currently in the process of developing a position paper on this important topic.

The report discusses the first Black Women’s Maternal Health Awareness Week which was organised by the Five X More campaign in September 2020. The campaign is effectively working to raise awareness by supporting and empowering Black women to make informed choices throughout their pregnancies. The campaign was set up in response to the racial inequalities experienced by two black mothers and the findings in the 2018 MBRRACE report (Please see the AIMS Journal article ‘MBRRACE and the disproportionate number of BAME deaths’ for more information on the 2018 MBRRACE report.[7]) Subsequently, AIMS teamed up with Five X More on a joint project to make sure that Black women know their rights within pregnancy and childbirth, to help achieve better outcomes for these women. AIMS and Five X More are volunteer organisations which are entirely independent of MBRRACE. However, MBRRACE have used data from Five X More. This shows that there is a change in conversation, which is a success of sorts, but it also feels as if the report has used this success to show actions which haven’t come from partners/sponsors of the report themselves.

RCM (Royal College of Midwives) and RCOG (the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists) have said that they are working to address racial disparities in the maternity services. The RCM have set up the ‘Race Matters’ initiative that sets out a five point plan which includes supporting research and championing positive change for those affected by racism in maternity. RCOG has set up a task force which aims to highlight where health care disparities exist and improve the understanding of these inequalities. They also aim to collaborate with the government to create meaningful solutions and improve the outcomes that are currently seen and experienced. It is not clear what these initiatives entail or what they have achieved so far.

NHS England/Improvement are in rapid development of a chart for use in England similar to the consensus Modified Early Obstetric Warning Signs (MEOWS) which monitors physical parameters for women and allows for early recognition of the deterioration based on these factors. These already exist and are in use in other parts of the United Kingdom. They are also creating clear response pathways to ensure appropriate escalation of care. It begs the question, why not just adopt the MEOWS strategy, particularly if there is evidence this is being successfully used?

Due to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, a rapid review was conducted of the care of all women who died with confirmed or suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection during or up to one year after pregnancy. This also included any women who died from mental health-related causes, or domestic violence which may have been influenced by the public health measures that were put in place to control the epidemic. Therefore, the MBRRACE report also included the actions following this rapid review. The rapid report showed evidence that Black and other women from ethnic minorities within the UK were disproportionately severely affected by COVID-19. NHS maternity units in England were requested to increase support, create tailored communications and discussions of nutrition, and to record ethnicity as well as other comorbidities on maternity information systems. However, no data was given on this in the MBRRACE report and also no evidence to show that this has in fact been actioned.

It is stated that other reviews have been actioned, however this is for information gathering only and none are currently funded to assess any outcomes or recommendations. It is, therefore, so important that campaigns are carried on by committed individuals and organisations in order to drive forward the much needed changes.

What does the report recommend?

Maternity care needs to improve in order to save lives. The recommendations from the MBRRACE assessors have been drawn directly from already existing guidance and reports. They have identified areas where the existing guidance needs to be strengthened and recommended actions where national guidelines are currently not available.

This report has gone back to focusing on the direct and indirect causes in a medicalised sense. It focuses on guidelines and ensuring that member organisations and professional groups support healthcare professionals in delivering these recommendations. Findings showed that almost three quarters of those women who died during or up to six weeks after pregnancy in 2016-18 had pre-existing physical or mental health conditions. One of the most concerning factors of the 2020 MBRRACE report is that there is very little discussion regarding pre-existing mental health conditions considering 198 of those 566 who died from 2016-18 experienced pre-existing mental health conditions. Maternal suicide is the fifth most common cause of death during pregnancy and up to six weeks after birth, and is the leading cause of death over the first year after pregnancy. There are no suggestions made in this report on how to improve access to services for pregnant women and people suffering with mental health conditions and how best to support them, and it is hard to determine from the report whether or not the type of birth was a risk factor for mothers.

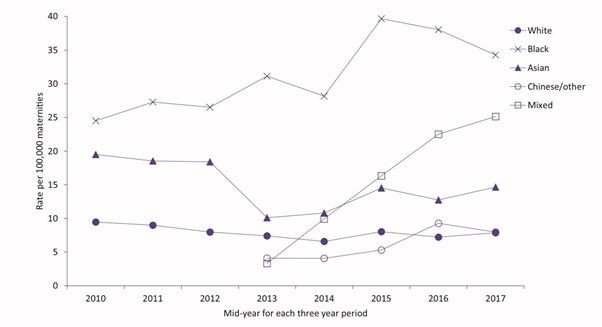

Although conversations around disparities in maternity care are improving and we are seeing campaigns from organisations such as Five X More raising awareness, it is extremely disappointing to see that this report has shown very little focus on continuing to reduce the maternal mortality rates and disparity by improving culture, attitude, and quality of care for non white people. While there has been a decrease (although not statistically significant) in the number of Black and Asian women who have died, there was an increase in the number of deaths of Chinese/other and Mixed Race people as shown in figure 3. We are still a long way off from seeing an actual reduction in mortality rates. Changes in conversation are not enough, action needs to be taken. There are no suggestions or comments in the report to work towards this change. It is only discussed that reports are being commissioned, meanwhile racial disparities in maternity care continue.

Figure 3 Maternal mortality rates 2009-18 among women from different ethnic groups in the UK

There also remains a statistically significant difference in maternal mortality rates between those living in the most deprived areas and those in the least deprived areas of the UK. It is suggested that this inequality gap is also increasing. Suggesting further research to fully understand the reason behind these disparities and develop actions to address them is a positive step, but suggestions are not enough.

Focusing on the physical causes of both direct and indirect deaths, the report makes numerous suggestions on changes in guidelines for all healthcare professionals. This is necessary and important for obvious reasons. Preventing the avoidable deaths of hundreds of pregnant women and people is what MBRRACE sets out to do. Hopefully the suggestions made will be implemented and achieve changes. It is important to remember that pregnancy and birth are generally very safe in the UK, but this report makes it clear that there is room for improvement.

Conclusions

Whilst assessors judged that 29% of the women who died had good care, they identified that in 51% of the deaths, had there been improvements in care, it may have made a difference to the outcome. It is clear that the level of care pregnant women and people are receiving simply needs to improve in maternity services within the UK.

There is a clear constellation of bias going on in maternity services within the UK. With 90% of those that died having other pre-existing physical and mental health conditions, there is systemic bias in the system that has led to these people failing to receive ‘good’ standards of care.

Additionally, there is no mention of anything in the recommendations to continue work on decreasing the disparities between Black and other ethnic minority pregnant women and people compared to their white counterparts. This has only been raised when comparing it to the new conversations about those with pre-existing medical conditions receiving a lower standard of care, and how this is not acceptable simply because they are pregnant.

The NHS and maternity services are facing continued constraints and challenges with increased births and health complexities of these, increased demand from policy changes, and the vicious cycle of staff shortages[8], all exasperated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The level of care that pregnant women and people receive will inevitably be affected. The RCM put forward solutions for these challenges but we are yet to see any improvement from the NHS and UK governments.

Guidelines and policies alone are not going to reduce mortality rates and disparities in these deaths. The constellation of bias, and racial and social disparities pregnant women and people are experiencing needs to change. Hopefully we will see in the next MBRRACE report that meaningful solutions have been put into practice, and that not only are we seeing a change in conversation, but also in positive action.

Author Bio: Megan is just beginning her journey as a student midwife and advocate for birthing people. She volunteers for AIMS on the Birth Information and Health Inequalities Teams. She lives in Essex with her young son.

[1] Editor’s note: For anyone not familiar with it, ‘Information about MBRRACE-UK for Parents and Health Service Users’ can be found here: https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/mbrrace-uk/service-users

[2] MBRRACE-UK (2020) Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care: Lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2016-18: https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/assets/downloads/mbrrace-uk/reports/maternal-report-2020/MBRRACE-UK_Maternal_Report_Dec_2020_v10_ONLINE_VERSION_1404.pdf

[3] MBRRACE-UK (2020) infographic and lay report. https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/assets/downloads/mbrrace-uk/reports/maternal-report-2020/MBRRACE-UK_Maternal_Report_2020_-_Lay_Summary_v10.pdf

[4] MBRRACE- UK (2020) Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care.

[5] Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy (SUDEP) is when a person with epilepsy dies suddenly and prematurely and no reason for death is found. https://sudep.org/sudden-unexpected-death-epilepsy-sudep

[6] Angus-Leppan H. (2019) ‘Epilepsy-related deaths and SUDEP’. Epilepsy Action. https://www.epilepsy.org.uk/info/sudep-sudden-unexpected-death-in-epilepsy

[7] McKenzie G. (2019) ‘MBRRACE and the disproportionate number of BAME deaths’. AIMS Journal. Vol 31. No 2

[8] Royal College of Midwives (2017) ‘The gathering storm: England’s midwifery workforce challenges’. https://www.rcm.org.uk/media/2374/the-gathering-storm-england-s-midwifery-workforce-challenges.pdf

The AIMS Journal spearheads discussions about change and development in the maternity services..

AIMS Journal articles on the website go back to 1960, offering an important historical record of maternity issues over the past 60 years. Please check the date of the article because the situation that it discusses may have changed since it was published. We are also very aware that the language used in many articles may not be the language that AIMS would use today.

To contact the editors, please email: journal@aims.org.uk

We make the AIMS Journal freely available so that as many people as possible can benefit from the articles. If you found this article interesting please consider supporting us by becoming an AIMS member or making a donation. We are a small charity that accepts no commercial sponsorship, in order to preserve our reputation for providing impartial, evidence-based information.

AIMS supports all maternity service users to navigate the system as it exists, and campaigns for a system which truly meets the needs of all.