AIMS Journal, 2019, Vol 31, No 4

By Paul Golden

Respecting birthing women’s rights

The law requires that birthing women and their families have their childbirth choices respected. Instead, they face challenging times. They experience conflict arising between their choices and the hospital. There are conflicts between guidelines and women’s wishes. Resolution to these conflicts can come from communication tools such as mediation-style communication. This article aims to provide women and families with some tools to help prevent and resolve conflict by using effective mediation communication techniques.

Mediation usually involves a third party who uses their communication skills to support people in reaching resolution. The mediator uses techniques that encourage communication and negotiation. However, these skills can be used without a third party to encourage positive, empathic communication. This can be by the woman herself in her interaction with maternity service staff, or by her partner, doula, midwife (employed or independent) or other supporter.

The informed consent and refusal process must include the freedom to consent to, or refuse, any and all treatments, including those that might be seen as life saving for the mother or baby. UK law protects the autonomy of the woman’s right to choose what she does with her body.

In the UK Supreme Court case of Montgomery v Lanarkshire in 2015,1 Lady Hale stated:

‘Gone are the days when it was thought that, on becoming pregnant, a woman lost, not only her capacity, but also her right to act as a genuinely autonomous human being.’

The summary of the case is that women have the right to be told information relevant to them. This ensures that they can make an informed decision. However, the way this has been interpreted by some clinicians is to use fear (and sometimes coercion) by telling the woman in an unbalanced way how she is putting her baby at risk. This is incorrectly seen as meeting the legal requirements to warn of all material risks, however slight. Responsibility for decisions needs to be held in partnership between women and staff with balanced, evidence-based information and respectful communication, and with the final decision itself being one that only the woman herself can make. By using some basic mediation skills, women and families can take more control of this process.

What is mediation?

‘Conflict is opportunity’ (Einstein).

Everyone is a mediator, a peacemaker. We behave as one naturally at home with our loved ones. When we fight in the morning, we make up by the evening. We listen, we allow others to express themselves so they will listen to us. We may feel better for venting. We find common goals by reframing what we are fighting about. There can be win-win solutions.

What if we are outraged by hospital rules, or feeling emotional? Maybe we think someone else would be better at mediating. In that case, use a third party if possible. This might be your partner, friend, family member or doula, and some consultant midwives or independent midwives can take this role – and you can always consider a professional mediator. However, all of us can mediate when there is only us to sort it out.

Create a framework for any hospital meeting, including being prepared for the unexpected. Consider using role play; perhaps video it on your phone, or rehearse in front of the mirror for any planned conversations about your wishes. This ‘training’ allows us to be flexible, assertive and clear. We may still react but we can pause and take a moment – even one breath – and then respond. This response, rather than reacting, will be more productive. We are mediating ourselves. We can fake it until we make it with calmness. The calmer we are, with inner confidence, the greater the influence on others around us. If we lose the calmness, we can walk away and either return later or get a third person to help.

We can control how we act ourselves, and we can possibly influence others, but we are not responsible for their actions. Using mediation communication ideas does not make women responsible for the way that the healthcare provider responds to them, but it might make the discussion more positive and may lead to a better outcome for all.

The key questions are, ‘What would you like?’ and ‘How are you?’. This genuinely empathetic questioning creates momentum from conflict to resolution through being cared about. We all wish to love and be loved. It is as fundamental as that. It is really important to understand where the other person’s position comes from, to respect that – but also to remember that their position, the issues that worry them, are their problem, not ones we need to take on. Understanding the pressures on the healthcare staff (e.g. concerns about being sued, pressure from management to get babies out and clear beds, pressures from the various ‘care bundles’, and so on) can help us to understand why they are saying what they say. This can help us to formulate a response that recognises their position, and when we show respect for the other person’s needs they are less likely to fight with us. Show that we are listening to them. Model and mirror positive behaviour – listening to someone helps them, in turn, to listen to us.

An example of this might be:

Hospital doctor: ‘You can’t go home. Your baby needs close observations of his sugars as he’s so small. He’s at risk.’

Mother: ‘I don’t need permission from you. I do need support and evidence-based information.’

She starts packing her bag, then, remembering mediation ideas, she says to the doctor, ‘What would you like?’.

By then listening to the reply, the mother shows that she is agreeing to engage with the doctor, which opens the door to a possible agreement.

Hospital doctor: ‘To monitor his blood sugars and ensure he’s feeding enough and warm enough and to protect him from infection.’

Mother: ‘Okay, what if … I will feed him at least every three hours and more if he asks, and we observe him. We can have the midwife visit, and take advice over whether a blood sugar test is required or not.’

Hospital doctor: ‘I’d prefer you both to stay. … But I can see that this is what you want so we can work with this.’

Mother: ‘Okay. I’m going home with my baby now.’

Afterwards, we hope that the doctor will reflect on the conversation and realise that they pushed the mother and could use better communication next time. The mother was angrily asserting her rights, but then she adopted a middle-path mediation communication style to listen to the perceived needs of the hospital and, by engaging, reached some agreement. The hospital had the choice of working with the woman or threatening to call children’s services. That would escalate matters. Both parties saw the benefit to the mother and baby of de-escalation. Now the mother agreed to allow a midwife to visit and support her with her baby at home on her terms. Whether this is called assertive advocacy or mediation doesn't matter. It is effective communication, including respectful listening, and agreement to discuss the issues even where that is only partial agreement.

When time is limited, we can focus on what we want rather than what we do not want. For example, if a long, possibly patronising explanation is being given to a woman about the risks she poses to her baby by ignoring hospital advice and guidelines, she can say: ‘I don’t need to hear more about that at the moment. I do need to focus on what I would like and how we can achieve this.’ Getting into arguments is unnecessary in many situations. Keeping to simple, open questions may be more likely to bring greater clarity. However much we mediate, sometimes we will not come to an agreement, and that is okay. The benefits of communicating are that this can continue to be built upon with greater trust later. Sometimes no words are required. Simply taking action can be all that’s necessary, such as leaving the hospital when you are told you must stay for a certain check. The staff are frequently stressed and afraid of various responsibilities (real and imagined). The language of hospital staff can sometimes be overly threatening and it can feel like they have all the power. Taking action is a great power balancer. The beliefs people have about their power is a power itself; therefore the ability to change that perception is also a source of power.

There may need to be some negotiated give and take. How you get what you want may depend on what you are prepared to give. This does not mean that you have to agree to an intervention in order to get what you want (for instance, you don’t need to agree to blood tests to be supported in a home birth). Rights are not up for negotiation in that way. Instead, try to work out where you can find agreement. That said, there are many situations where no negotiation is necessary, and a simple ‘No’ is required. When we avoid saying no, our bodies pay the price.

While it can be tempting to share the detailed information you may have researched, often situations around pregnancy and birth are charged with emotions, making it potentially upsetting to debate the merits of research. Having said that, sometimes bringing out a copy of the WHO, NICE or local trust guideline that contradicts the advice a midwife or doctor is giving might be helpful. For instance, my experience is that providing a NICE guideline stating that ultrasound scans are not required in a particular case has helped some clinicians to relax their insistence on scans.

The reports I have seen3,4 about culture and hierarchy leading to bullying and clinical failings suggest a system that is slow to change. It is therefore imperative that parents challenge their caregivers to provide evidence, clear rationales and evidence for any intervention, including the possible risks and alternatives. Hopefully the skills shared above will help parents to do this in a way that is beneficial to them – although again remembering that healthcare practitioners are fully responsible for their actions, and if they are unkind, or if they do not engage appropriately with parents, that is solely their responsibility. They are then answerable to their regulators (GMC or NMC) and/or employers.

NHS and independent mediation services

Some hospitals are engaging with mediators. St Thomas’ Hospital London, for instance, has a mediation service to help parents and staff. The mediator can ‘shuttle’ between parties, which is useful for saving face in certain cases where parties prefer not to see each other.

The role of the midwife as an advocate (UK NMC Code 3.4) can be compromised by defensive midwifery practice focused on the midwife keeping their job; however, NMC Code 4.1 states that midwives should ‘balance the need to act in the best interests of people at all times with the requirement to respect a person’s right to accept or refuse treatment’.

Doulas are often in a wonderful position with the opportunity to liaise or mediate with staff. Simply being there with calm confidence can have a positive ripple effect. The hospital staff have another pair of eyes shining a light on how they practise. A raised eyebrow, a tilting of the head, any useful compassionate engagement can get the staff to reconsider the true necessity of an action.

Birth Afterthoughts services

Some hospitals have Birth Afterthoughts services, which aim to help women to understand why certain things happened. These services can be valuable to women in helping them to understand what happened in their birth, and, done well, with good mediation skills, can be a helpful communication process. Some NHS trusts use PALS or Afterthoughts to protect them from litigation rather than resolve issues. The Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman5 is a useful way to record and escalate unresolved NHS complaints.

NHS Resolutions

NHS Resolutions is the new name for the NHS Litigation Authority. Does that mean it uses mediation? To a small extent yes, but in general it is about reducing costs of litigation rather than reaching agreements. It is often accused of being adversarial and purposefully delaying cases to get beyond the three-year civil liability threshold. It is even known for threatening traumatised families with high court costs if they challenge the NHS.

In 2017-2018, the NHS was faced with claims of £2.1bn on cases of maternity-related clinical negligence. Compare that to the £1.9 billion per year that is spent on birth care.’6

Mediation would be a great way forward in saving NHS funds but, more importantly, in restoring the balance of power, with consumers being listened to and lessons being learned by the NHS. There are plans to adopt the rapid resolutions model from Sweden. That would give more rapid closure and learning for families and staff.

Midwifery resolution in New Zealand Aotearoa as a model to adopt

In New Zealand, birthing and pregnant women and their families can make a low-level complaint to the New Zealand College of Midwives (NZCOM) Resolutions Committee.7 This was started by midwives and local consumer representatives to make an easier process for resolving concerns. This is achieved with third-party clarification by the midwife as mediator. They can make professional recommendations only as they do not have any disciplinary powers. It is the process of actively listening and following up with feedback to both parties by the mediator which facilitates resolution. (If it were simply listening without action, it would be counselling.) This form of resolution is an example of humanistic shuttle mediation where the midwife as mediator sees both parties separately and is focused on active listening. The mediation is non-directive and dialogue-driven. I have proposed this to the UK’s Royal College of Midwives without success so far. So, for now, it is down to us to mediate ourselves, finding others to mediate when possible.

Conclusion

Women do have choices and rights in childbirth. They can sometimes go to another provider. They can birth out of hospital at home, and many women can birth in a midwifery unit or birth centre. Getting the best from our carers can sometimes depend upon how we discuss what we would like. All women should be treated with respect and dignity no matter how they approach their care. In general, the law assumes and provides for parental responsibility and mental capacity. When we all stand up for our human rights and help others by shining a light when there are challenges, we create the change we wish to see. Let us create opportunities to transform fear into the courage to love through mediating peacemaking with compassionate communication.

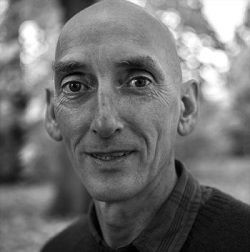

Paul Golden is a global midwife lecturer and professional mediator. He offers birth mediation courses for healthcare providers, midwives, doctors, doulas and families (online and in person). He is an expert witness report writer globally attending court and regulatory proceedings.

REFERENCES

1. Montgomery v Lanarkshire Health Care [2015] UKSC 11

2. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/10/171030095422.htm

3. Morecambe Bay Maternity Investigation Report https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/408480/47487_MBI_Accessible_v0.1.pdf

4. Review of Maternity Services at Cwm Taf Health Board https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2019-04/review-of-maternity-services-at-cwm-taf-health-board_0.pdf

5. https://www.ombudsman.org.uk/

6. https://www.hsj.co.uk/saving-babies-lives/7024392.article

7.https://www.midwife.org.nz/midwives/college-roles-and-services/resolutions-committee/

FURTHER READING

The Dynamics of Conflict Resolution: A Practitioner’s Guide by Bernard S. Mayer 2012 Pub. Jossey-Bass

The AIMS Journal spearheads discussions about change and development in the maternity services..

AIMS Journal articles on the website go back to 1960, offering an important historical record of maternity issues over the past 60 years. Please check the date of the article because the situation that it discusses may have changed since it was published. We are also very aware that the language used in many articles may not be the language that AIMS would use today.

To contact the editors, please email: journal@aims.org.uk

We make the AIMS Journal freely available so that as many people as possible can benefit from the articles. If you found this article interesting please consider supporting us by becoming an AIMS member or making a donation. We are a small charity that accepts no commercial sponsorship, in order to preserve our reputation for providing impartial, evidence-based information.

AIMS supports all maternity service users to navigate the system as it exists, and campaigns for a system which truly meets the needs of all.