To read or download this Journal in a magazine format on ISSUU, please click here

AIMS Journal, 2018, Vol 30, No 3

By Marta Busquets

Throughout history there have always been some babies who were not breastfed by their own mothers, for many different reasons. The main solution was found in a woman who was not the mother of the baby, often family members or friends; for instance, a woman breastfeeding her sister’s baby.

Babies were only fed animal milk when human milk was not available. It was often milk from goats, horses or sheep, although, in the vast majority of cases, cow’s milk. Around one third of the non-breastfed babies died, and the ones that survived were more prone to being sickly.1

Despite the clear evidence of the problems that non-human milk causes to human babies, in 1867 Justus von Liebig created and patented the first commercial infant formula and only sixteen years later there were 27 patented different brands and strong marketing pushing the products. What really started the revolution was the need to find a market for the now excessive quantities of cow’s milk which was being produced, thanks to greater efficiencies in milk farming. The market needed to be created, and Henri Nestlé was ready to make it. He created a food called “Farine Lactée” which was made from wheat flour and condensed milk. Not surprisingly, Mr Nestlé was a grain merchant, so this product suited him well as an outlet for his grain, together with the glut of milk around at the time. “Farine Lactée” was heavily marketed as a healthy food for infants, alongside the claim that it had saved the life of a baby whose mother was unable to breastfeed him. Whether this claim is true, we don’t know, but there were no advertising standards at that time…

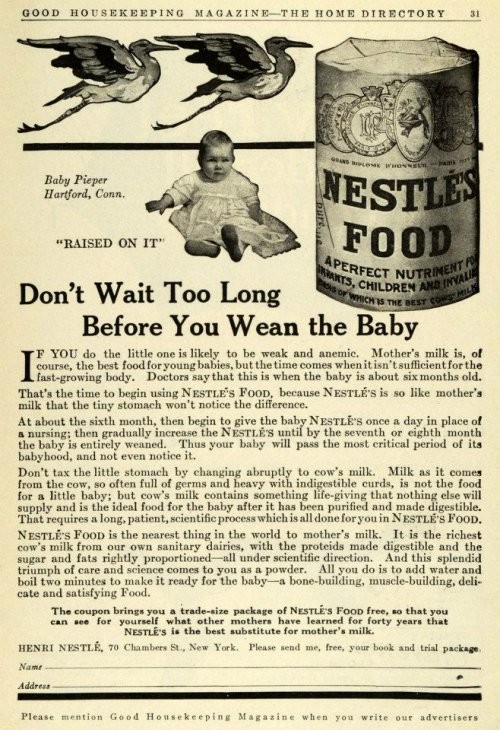

Advertising at the time not only made the dangerous and inaccurate statement that artificial formula was equal to mother's milk, it actually got to a point where it claimed that it was better or more convenient than breastmilk or breastfeeding. It was presented as a healthy choice (it is still marketed the same way today), with the description that it was a scientifically-made product which would resolve their invented claim that “the time comes when it isn’t sufficient for the fast-growing body” (see image). By the early 1900s there was some indication that there was a desire to suppress some of the more outrageous claims about milk products marketed for babies, and the 1911 “Report on the unsuitability of sweetened condensed milk” was discussed in the UK’s Parliament. Following this, the requirement to label condensed milk with “unsuitable for infants” was made law, but one manufacturer printed, “For Infants and Invalids” in huge letters, with the “unsuitable for infants” in tiny text.2

Advertising at the time not only made the dangerous and inaccurate statement that artificial formula was equal to mother's milk, it actually got to a point where it claimed that it was better or more convenient than breastmilk or breastfeeding. It was presented as a healthy choice (it is still marketed the same way today), with the description that it was a scientifically-made product which would resolve their invented claim that “the time comes when it isn’t sufficient for the fast-growing body” (see image). By the early 1900s there was some indication that there was a desire to suppress some of the more outrageous claims about milk products marketed for babies, and the 1911 “Report on the unsuitability of sweetened condensed milk” was discussed in the UK’s Parliament. Following this, the requirement to label condensed milk with “unsuitable for infants” was made law, but one manufacturer printed, “For Infants and Invalids” in huge letters, with the “unsuitable for infants” in tiny text.2

In the 1970s the rate of breastfeeding was extremely low - in the US, around 75% of babies were bottle-fed in that period. During that time companies started expanding into developing countries with even fewer regulations and controls, which made more aggressive marketing possible. Formula feeding increases the chance of illness and death and the chances are much worse for children in areas with unhygienic conditions, dirty water and families forced to dilute the formula because it’s too costly. According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF)3, a formula fed child in such precarious conditions is 25 times more likely to die of diarrhoea and 4 times more likely to die of pneumonia than a breastfed one. In the “developed” world, a formula fed child is also at a 25% increased risk of death compared to a breastfed baby.4 Besides the death rates, formula feeding increases the risk of asthma, allergies, lower cognitive development, breathing infections, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, childhood cancer (in particular, leukaemia), chronic diseases and anaemia. Despite these risks, formula companies such as Nestlé disguised sales women as nurses, leading parents to believe that the artificial milk that they were selling was medically approved. Following the theme of using medical staff to support the sale of formula, doctors have received commissions or presents for encouraging formula feeding and women have been given formula samples in hospital which interfere with their own milk production, thus creating an unnecessary need and making mothers dependent on the product. By advertising in medical centres and birth centres, formula appeared to be medically endorsed. Doctors started to see malnutrition, serious illness and death in babies with a frequency never before seen. They called it “bottle baby disease”.5

In 1973 a magazine called the New Internationalist was published. A booklet titled ‘The Baby Killer’ followed a year later. Both of them exposed these illegal and unethical practices to the public. This was the start of protests that led in 1977 to a Nestlé boycott, initially launched from the United States of America, but which was quickly picked up in other countries. The Nestlé Boycott6 continues to be followed across the world to this day: as Nestlé is one of the biggest manufacturers of infant formula, and its marketing leads babies to be put at risk by claims that it makes, such as that its formula “protects babies”.6 Gabrielle Palmer’s ‘Why The Politics of Breastfeeding Matter’ states, ‘A Swiss action group called its version [of The Baby Killer] “Nestlé kills babies” […] Nestlé at first charged the group on four counts of libel: the title; the accusations of unethical practices; responsibility for death or damage to babies; and dressing saleswomen as nurses. By the final court hearing Nestlé had withdrawn all charges except for the title. The judge ruled this libellous because members of the Nestlé company had not actually killed babies; the mothers had done the killing when they bottle fed them with the artificial milks.’

In 1981, all of the above prompted the World Health Assembly to establish the International code of Marketing of Breastfeeding Substitutes7 which tries to establish ground rules regarding the marketing and promotion of such food products directed to babies and infants and limit the illegal and unethical approaches. Some of the items in the code have been introduced into UK law, including making it illegal to advertise or promote infant formula - which is why parents cannot buy discounted infant formula, nor get benefits such as supermarket reward card points on it.

Since then, different initiatives and regulations have been established internationally and locally to protect and promote breastfeeding from aggressive marketing, and to make formula risks available and known to the general public. For example, UNICEF, together with the World Health Organisation (WHO), launched the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) in 1991. In order for a hospital to get accredited it has to ensure that it provides adequate breastfeeding support and respects the aforementioned International code of Marketing of Breast-feeding Substitutes. Thanks to these initiatives, breastfeeding rates have been slowly recovering in many developed countries over recent decades, even though formula companies continue violating regulations through sophisticated and subliminal marketing methods.

According to the UK regulations, formula manufacturers cannot advertise formula for newborns, so they created different formulas according to age groups. By referring to Stage 2 formula (“Follow on”) or Stage 3 (“Toddler milk”) they can be advertised since it is aimed at babies older than six months – but the packages and merchandising are almost exactly the same as stage 1 formula, and in the adverts they very often use babies that appear to be under six months even though they will be older babies.

They have also once again expanded their business and unethical tactics to developing countries. But campaigners are fighting back. Such behaviour has sparked new boycott calls against formula companies in general and Nestlé in particular.8

As well as the Nestlé boycott, we are seeing open discussions on the environmental footprint of formula production, since it produces high amounts of waste, greenhouse gases (remember that the cattle industry is the second largest contributor to such gases) and water consumption (a minimum of 4.000 litres of water are needed to produce just 1kg of formula powder). Breastfeeding charities including The Association of Breastfeeding Mothers, La Leche League, Breastfeeding Network and the NCT continue to train people to a very high level to support women who want to breastfeed. These courses not only cover the practical skills of breastfeeding, and resolving breastfeeding issues with babies and children from birth to weaning, but include counselling training in order to help women to support their own goals. With these skills, and the sharing of these skills, we are reclaiming the woman to woman support and knowledge which has been, for so long, deliberately undermined by the formula companies.

But, the fight is far from over. It is important that governments, health agents, organisations and women keep demanding that regulations be respected and commit to contributing to a strong breastfeeding culture, including a social climate where women decide with all information available and babies are not victims of unethical marketing tactics. The Nestlé boycott continues, and AIMS is one of many organisations which ensures that no Nestlé product is used at any of its meetings, and many members also follow this ban in their own homes. Maybe you would like to join the boycott and ditch Nestlé?

Marta Busquets is a lawyer from Barcelona specialising in health and gender, and an advocate for women's rights, focusing on sexual and reproductive rights including breast-feeding.

Further reading:

The AIMS Journal spearheads discussions about change and development in the maternity services..

AIMS Journal articles on the website go back to 1960, offering an important historical record of maternity issues over the past 60 years. Please check the date of the article because the situation that it discusses may have changed since it was published. We are also very aware that the language used in many articles may not be the language that AIMS would use today.

To contact the editors, please email: journal@aims.org.uk

We make the AIMS Journal freely available so that as many people as possible can benefit from the articles. If you found this article interesting please consider supporting us by becoming an AIMS member or making a donation. We are a small charity that accepts no commercial sponsorship, in order to preserve our reputation for providing impartial, evidence-based information.

AIMS supports all maternity service users to navigate the system as it exists, and campaigns for a system which truly meets the needs of all.