AIMS Journal, 2023, No 35, No 2

By Kathryn Kelly

Introduction

Until relatively recently, women[1] gave birth at home as the norm and only used a ‘maternity home’ or hospital if they had social or medical needs or could afford the private fee. In 1946, 46% of births in England and Wales were at home, with the balance in a maternity home or hospital. [2]By 1970 birth at home was down to 13%, and in GP units 12%. By 1990 home birth was at 1%, and GP Units 1.6%.[2] In her seminal statistical analysis of birth data, Tew describes the “almost universal misunderstanding” of what the evidence showed, that “birth is the safer, the less its process is interfered with”.[2]

Data for 2021 shows that 97% of parents in England and Wales gave birth in an NHS establishment,[3] with a home birth rate of 2.5%,[3] but despite this wholesale move to a perceived place of safety, anecdotally anxiety about birth appears to be rising alongside the intervention rate.

The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) states that women should have access to four planned places of birth: Home, Freestanding Midwife-Led Unit (FMLU), Alongside Midwife-Led Unit (AMLU), and Obstetric Unit (OU). While NICE considers that women at low risk of complications are free to decide on place of birth, it suggests that those with certain risk factors should be given information about those risks before being supported in their decision. It states that personal views or judgements of the healthcare provider should not be shared.[4]

When we talk about safety in childbirth, most people think of a ‘healthy baby’, with ‘healthy’ as a euphemism for ‘live’, and perhaps as an afterthought a ‘healthy mother’. Parents I speak with who have already given birth are more likely to prioritise factors such as psychological safety, cultural safety, and a sense of control.

In this article I intend to explore what research tells us about place of birth and safety for babies and mothers. I will also consider the wider factors involved, as well as what makes birth unsafe and who are we keeping safe.

Definitions and statistics – for the baby

Let’s start with some definitions and, because all definitions are situated within time and place, context.

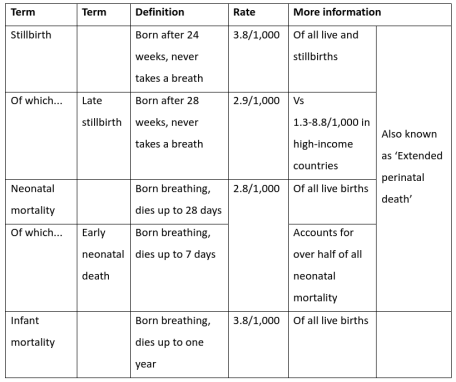

Table 1. Definitions and statistics of stillbirth and infant mortality in the UK in 2023. [3],[5],[6],[7],[8]

MBRRACE-UK shows the causes of stillbirth to be relatively consistent over the period 2016-2020:[7]

Unknown causes are reducing, but still over 30% of all stillbirths

Related to the placenta (over 30%)

Congenital anomalies (under 10%)

Other conditions: fetal, cord, infection, maternal (each around 5%)

Intrapartum (around 2% of all stillbirths)

Intrapartum death is a tiny component of the ‘safety’ dimension

An intrapartum death describes the rare situations when the baby was assessed as alive at the onset of labour, but dead at birth. Even if we add intrapartum stillbirths and neonatal deaths due to intrapartum causes, we still arrive at a rate of less than 0.1 per 1,000 live and still births.[7] While acknowledging that every death is a huge and painful loss, we can also see that there is a very rare chance of it happening.

For the mother

As Winnicott identified, maternal wellbeing is critical to the baby as they adjust to life outside the womb.[10]

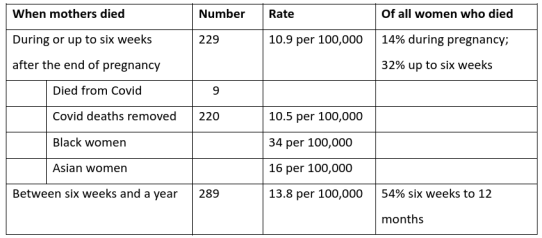

Table 2: Maternal mortality in the UK, 2018-2020.[11]

The MBRRACE review of maternal mortality in 2018-2020 includes a table of place of birth.[11] This shows that 5 (4%) of the women who died had given birth at home, and only one of those had died of ‘direct causes’ (a wide definition which includes thrombosis, suicide, sepsis, and haemorrhage).[12] The remainder gave birth either in hospital, the emergency department, or an ambulance. This data is not shown by ‘intended’ place of birth, so we should acknowledge that more of the deaths could be associated with place of birth, though the variety of ‘direct causes’ might suggest that a good quality and well supported out-of-hospital birth service would not be a contributing factor.

What about the safety of the health professional?

Protecting midwives is sometimes given as the reason for withdrawing the home birth service when the maternity or ambulance services are compromised. Understandably, a Director of Midwifery doesn’t want to put their staff in a situation without good backup. There is also enormous pressure for documented adherence to guidelines, to protect both individual healthcare workers and the service provider from the fear of withdrawal of employment or litigation.

With the harm of long-term exposure to Entonox in the news this year, ‘safety’ takes on another perspective. Midwives may be working in older hospitals without adequate scavenging systems that remove harmful gases.[13] For them, a home or midwife-led unit with windows providing fresh air could be protective.

What reduces or mediates safety?

Most stillbirths occur in pregnancies without established risk factors.[8] So what reduces that safety, and what protects it?

Routine antenatal care looks for the key factors associated with poor outcomes for the mother or baby. Early scans and blood tests look for congenital abnormality, and monitoring of the baby’s growth checks whether that slows or stops. Monitoring of the mother’s blood pressure and urine check for pre-eclampsia. In the event of any concern, or when labour starts before 37 weeks, it’s recommended that care is provided on the obstetric unit, and parents can accept or decline that increased level of medical care.

We know that previous birth experiences have a significant impact, both on risk status and the perception of safety.[14] A first-time mother or pregnant person is known as nulliparous (nullip), and someone who has given birth before is multiparous (multip). Even with a more complicated pregnancy, a multip (except by caesarean) is less likely to have a complicated birth in a subsequent pregnancy, while a woman who has had a previous caesarean is considered to have the same risk status as a nullip.

For the unexpected outcomes we can ask why place of birth would have an impact? The resources at home and midwife-led units are identical. An analysis of intrapartum deaths at home and in MLUs found that risk assessment in pregnancy or early labour could be improved, along with a better standard of monitoring, resuscitation, and timely transfer.[15] So, while staff at different locations should have the same skills - and they routinely conduct ‘skills drills’ to practise for emergency situations - there is scope for improvement. But the most significant factor is time and distance from speedy intervention if it’s needed, which I will explore later.

While the planned place of birth is captured in the raw data, it is not currently shown as a risk factor for infants. What we do know is that stillbirth has been rising since 2010 for the poorest families, while it falls for the more advantaged. “The stillbirth rate in the 10% most deprived areas in England was 5.6 stillbirths per 1,000 births in 2021; in contrast, the stillbirth rate was lower in the 10% least deprived areas in England at 2.7 stillbirths per 1,000 births”.[3] The UK has a high level of inequality (when compared with economically similar countries) and lower socioeconomic groups are less likely to access antenatal care promptly, more likely to smoke and to be obese.[6] There is also an association between deprivation, stress, domestic abuse, and small or premature babies and late stillbirth.[16],[17]

Ethnicity is a significant factor: “Babies from the Black ethnic group continued to have the highest stillbirth rate at 6.9 stillbirths per 1,000 births in 2021”.[3] Since the MBRRACE-UK report published in 2020 there has been a spotlight on the need to address ethnic disparities (which were already present but not highlighted). While this is partly laid down to socioeconomic deprivation, that doesn’t fully explain it. For example, research with migrant women illustrated the need for clear and consistent protective messages.[18]

Just as with babies, mothers with severe disadvantages are over-represented in the data, and 20% of women who died were “known to social services”.[3] These were known vulnerabilities, which makes this even more unacceptable. Black, Asian, and mixed-ethnicity women are over-represented in the numbers, and while there is intersection with other vulnerabilities, this doesn’t explain it all. Ina May Gaskin points out that women’s bodies are not “inadequate” to birth, and this remains true of Black and Asian women and babies, so we need to understand how weathering[19] and gendered racism are leading to these worse outcomes.[20]

Social disparities are not only more difficult to resolve, they are also public health issues outside the remit of maternity services. So, while Continuity of Care (CoC) teams may be established to focus on providing holistic support to groups with identified medical or social needs, healthcare providers tend to focus on more easily measured factors, such as smoking, obesity, and high blood pressure. However, “target driven care can be actively harmful”.[21]

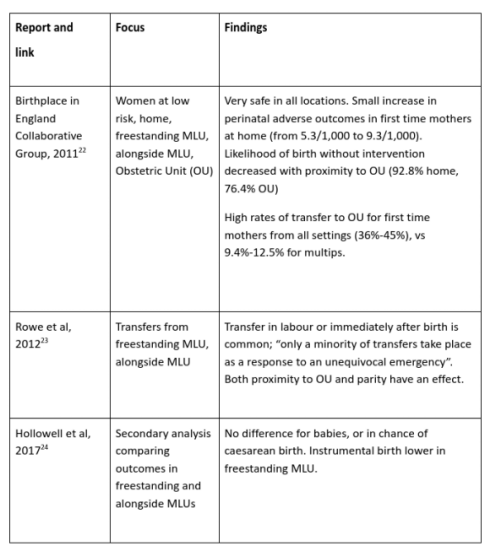

What’s the best source of information about place and safety?

‘Birthplace in England’ was a large and robust study that looked at where women had planned to give birth and what the outcomes were.[22] While it may feel to parents that a report published in 2011 is ‘old’, there has been no update and it remains the ‘go-to’ source for this specific information. By analysing outcomes by ‘planned’ place of birth it showed all outcomes, wherever birth finally took place, which makes it an interesting resource. When we compare newer research, we have to bear that point in mind.

There were several analyses of the data collected. In the report, ‘perinatal and maternal outcomes by planned place of birth for healthy women with low-risk pregnancies’, four planned places of birth were included: Home, FMLU, AMLU (in the same building as the OU, though sometimes not on the same floor), and OU (commonly known as ‘Labour Ward’). The OU is the only place doctors will be found, though most of the care is still undertaken by midwives.

Table 3: Summary of Birthplace findings for women with ‘low risk pregnancies’ [23], [24]

The top line from the first published study was that “giving birth is generally very safe”.[25] This explored the experience of women with ‘low risk’ pregnancies, and a primary outcome of “perinatal mortality and specific neonatal morbidities: stillbirth after the start of care in labour, early neonatal death, neonatal encephalopathy, meconium aspiration syndrome, brachial plexus injury, fractured humerus, and fractured clavicle”.[22] This composite was designed to capture outcomes that might be related to quality of intrapartum care, and includes those factors which could potentially have a long-lasting impact on the baby and family.

The study found that for multips there was no difference in adverse outcomes across all four places of planned birth. For nullips there was a small but significant increase in adverse outcomes for the baby if birth was planned at home (4 in 1,000 babies).[22]

For the secondary outcome of “neonatal and maternal morbidities, maternal interventions, and mode of birth” the finding was that women who planned births off the obstetric unit were much less likely to experience “an instrumental or operative delivery or to receive medical interventions such as augmentation, epidural or spinal analgesia, general anaesthesia, or episiotomy”.[22] I find it’s often necessary to remind parents at this point that all the women started with the same ‘low risk’ factors, so those on the obstetric unit were not having these procedures because they ‘needed’ them at the start of labour.

A useful decision aid for birth workers and parents is Dr Kirstie Coxon’s graphic, which illustrates both primary and secondary outcomes.[26]

I mentioned earlier that time and distance from emergency care could be considered the only point when place of birth might have a safety dimension. For context, the top three reasons for transfer from either FMLU or AMLU are not for emergencies but a cautious response to a slower than expected labour or meconium staining, or for access to epidural pain relief (especially in AMLU).[23] Much less common were reasons such as fetal distress in the first stage (4 or 6 in the list), or postpartum haemorrhage (9 or 10 in the list). First time mothers (especially older nullips) were more likely to transfer, and the authors theorise that this may have been down to care-provider caution.

For women considering the difference between freestanding MLU and alongside MLU, a secondary analysis showed no significant difference in adverse outcomes for babies, or chance of caesarean birth.[24] Instrumental birth (forceps or ventouse) was lower in freestanding settings.

Let’s talk about ‘low risk’

Much like the fact that most medical research is conducted on men because they don’t have pesky hormonal cycles that might muddy the waters, most place of birth research looks at women with ‘low risk’ pregnancies. The Birthplace study used the NICE definition to identify women with conditions that may lead to higher risk status.[4]

A 2014 study found that 45% of women would have been considered low risk using these definitions, so even then, any guidance aimed at ‘low risk’ women already applied to less than half the birthing population.[27] Since then, we’ve had a pandemic which resulted in a dramatic reconfiguration of maternity services, and an increase in poverty and social disparities. Research has not yet been published that would address how these changes might affect risk. Nor has there been a recent exploration of whether these definitions of higher risk remain valid.

In the next article I discuss the majority who are regarded as not having a low-risk pregnancy, and look at other factors we need to consider.

Author bio: Kathryn Kelly has been a self-employed NCT Antenatal practitioner since 2009, and also works for NCT creating and curating CPD for practitioners. She has a particular interest in learning and writing about perinatal informed decision-making.

[1] This article is based on research and other sources that refer only to ‘women’.

[2] Tew M (1998) Safer Childbirth?: a critical history of maternity care. (2nd Edition). London. Free Association Books Ltd.

[3] Office for National Statistics (ONS), released 19 January 2023, ONS website, statistical bulletin, Birth characteristics in England and Wales: 2021. Worksheets 1 and 17. www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/livebirths/datasets/birthcharacteristicsinenglandandwales

[4] NICE (2014) Intrapartum care for healthy women and babies [CG190]. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg190

[5] Morris J (2018) Understanding the health of babies and expectant mothers. Nuffield Trust. www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/resource/understanding-the-health-of-babies-and-expectant-mothers#how-do-stillbirth-and-infant-mortality-rates-compare-internationally

[6] Draper ES, Gallimore ID, Smith LK, Matthews RJ, Fenton AC, Kurinczuk JJ, Smith PW, Manktelow BN, on behalf of the MBRRACE-UK Collaboration. MBRRACE-UK Perinatal Mortality Surveillance Report, UK Perinatal Deaths for Births from January to December 2020. Leicester: The Infant Mortality and Morbidity Studies, Department of Health Sciences, University of Leicester. 2022 www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/mbrrace-uk/reports

[7] Nuffield Trust (2023) Stillbirths and neonatal and infant mortality.

www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/resource/infant-and-neonatal-mortality#background

[8] O’Brien, L, Warland J, Stacey T, Heazell AEP, Mitchell EA. (2019) Maternal sleep practices and stillbirth: Findings from an international case-control study. Birth. 46 (2) pp344-354. doi.org/10.1111/birt.12416

[9] Editor’s note: The full definition of “stillborn child” in England and Wales is contained in the Births and Deaths Registration Act 1953 section 4 as amended by the Stillbirth (Definition) Act 1992 section 1(1) and is as follows: “a child which has issued forth from its mother after the 24th week of pregnancy and which did not at any time breathe or show any other signs of life”. Similar definitions apply in Scotland and Northern Ireland. www.parliament.uk/globalassets/documents/commons-library/Registration-of-stillbirth-SN05595.pdf

[10] Jan Abram (2008) Donald Woods Winnicott (1896–1971): A brief introduction, The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 89:6, 1189-1217. doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-8315.2008.00088.x

[11] Knight M, Bunch K, Patel R, Shakespeare J, Kotnis R, Kenyon S, Kurinczuk JJ (Eds.) on behalf of MBRRACE-UK. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care Core Report - Lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2018-20. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford 2022. www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/mbrrace-uk/reports

[12] Indirect causes included cardiac, covid, neurological, and other.

[13] RCM (No date) Entonox safety in the workplace, administration equipment, scavenging and ventilation systems, occupational exposure levels. www.rcm.org.uk/workplace-reps-hub/health-and-safety-representatives/entonox-safety-in-workplace-1/

[14] Jardine et al (2020) Risk of complicated birth at term in nulliparous and multiparous women using routinely collected maternity data in England: cohort study. BMJ. 371. doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3377

[15] Rowe, R. et al. (2020) ‘ Intrapartum related perinatal deaths in births planned in midwifery led settings in Great Britain: findings and recommendations from the ESMiE confidential enquiry.’, BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 127(13), pp 1665- 1675. Available at: obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1471-0528.16327

[16] Heazell, AEP, Budd, J, Smith, L, Li, M, Cronin, R, Bradford, B, McCowan, L, Mitchell, E, Stacey, T, Roberts, D & Thompson, J 2021, 'Associations Between Social and Behavioural Factors and the Risk of Late Stillbirth – Findings from the Midland and North of England Stillbirth Case-Control Study', BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, vol. 128, no. 4, pp. 704-713. doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16543

[17] Stacey, T., Prady, S., Haith-Cooper, M. et al. Ethno-Specific Risk Factors for Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes: Findings from the Born in Bradford Cohort Study. Matern Child Health J 20, 1394–1404 (2016). doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-1936-x

[18] Stacey, T, Haith-Cooper, M, Almas, N & Kenyon, C 2021, 'An exploration of migrant women’s perceptions of public health messages to reduce stillbirth in the UK: a qualitative study', BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, vol. 21, no. 1, 394. doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03879-2

[19] Editor’s note: For an explanation of weathering (being worn down by) in this context, read: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1470581/

[20] Patterson, E.J., Becker, A. & Baluran, D.A. Gendered Racism on the Body: An Intersectional Approach to Maternal Mortality in the United States. Popul Res Policy Rev 41, 1261–1294 (2022). link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11113-021-09691-2

[21] Downe S, Byrom S (2019) Normal Birth; what's going on? 4 Jul. Maternity and Midwifery Forum. youtu.be/Qy5RTDuHdvs

[22] Birthplace in England Collaborative Group, Brocklehurst P, Hardy P, Hollowell J, Linsell L, Macfarlane A, Mccourt C, Marlow N, Miller A, Newburn M, Petrou S, Puddicombe D, Redshaw M, Rowe R, Sandall J, Silverton L, Stewart M. Perinatal and maternal outcomes by planned place of birth for healthy women with low risk pregnancies: the Birthplace in England national prospective cohort study BMJ 2011; 343 :d7400 doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d7400

[23] Rowe R, Fitzpatrick R, Hollowell J, Kurinczuk J. Transfers of women planning birth in midwifery units: data from the Birthplace prospective cohort study. BJOG 2012;119:1081–1090. doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03414.x

[24] Hollowell, J., Li, Y., Bunch, K. et al. A comparison of intrapartum interventions and adverse outcomes by parity in planned freestanding midwifery unit and alongside midwifery unit births: secondary analysis of ‘low risk’ births in the birthplace in England cohort. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 17, 95 (2017). doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1271-2

[25] NPEU (No date) Birthplace in England research programme: key findings. www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/birthplace#the-cohort-study-key-findings

[26] Coxon, Kirstie. (2015). Birth place decisions: Information for women and partners on planning where to give birth A resource for women and clinicians. doi.org/10.13140/2.1.3522.5929

[27] Sandall J, Murrells T, Dodwell M, Gibson R, Bewley S, Coxon K, Bick D, Cookson G, Warwick C, Hamilton-Fairley D. The efficient use of the maternity workforce and the implications for safety and quality in maternity care: a population-based, cross-sectional study. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2014 Oct. PMID: 25642571. doi.org/10.3310/hsdr02380

The AIMS Journal spearheads discussions about change and development in the maternity services..

AIMS Journal articles on the website go back to 1960, offering an important historical record of maternity issues over the past 60 years. Please check the date of the article because the situation that it discusses may have changed since it was published. We are also very aware that the language used in many articles may not be the language that AIMS would use today.

To contact the editors, please email: journal@aims.org.uk

We make the AIMS Journal freely available so that as many people as possible can benefit from the articles. If you found this article interesting please consider supporting us by becoming an AIMS member or making a donation. We are a small charity that accepts no commercial sponsorship, in order to preserve our reputation for providing impartial, evidence-based information.

AIMS supports all maternity service users to navigate the system as it exists, and campaigns for a system which truly meets the needs of all.