AIMS Journal, 2024, Vol 36, No 3

By Alex Smith

Welcome to the September 2024 issue of the AIMS journal. The theme for this quarter explores different aspects of trust encountered in the course of a person's maternity care.

Bringing a baby into the world is fraught with uncertainty, and always has been. Do I really want this? Will I find the support I need? Will the pregnancy go to term? Will the baby be all right? Will I survive this? Will my partner-relationship (if there is one) survive this? Will I still have a job? Will I be a good parent? Will I be able to provide for another person? And, an uncertainty down the generations, will the world be a safe place for my baby? The honest answer to all of those questions is, ‘probably, hopefully, I trust it will, but who knows?’.

Uncertainty is part of life. It is natural and inevitable, and we weigh probabilities every time we climb the stairs, cross the road or use a toaster. While our mothers may secretly worry about us, we generally get used to living with these everyday uncertainties; we generally learn to trust ourselves. In pregnancy however, self-trust is systematically undermined. From the moment of conception we are taught to defer decision-making to the midwife and doctor, and to the birth technology - it is as if the mother is merely an incubator and cannot be trusted with responsibility for the baby, but that is not the case in law. With very rare exception, even when we might actively want to abdicate responsibility and appoint ‘experts’ to make the best decisions, the appointment of those other people, and whether or not we comply with their advice, require ‘master’ decisions that are ours and ours alone to make. However much we may want to trust the doctor or midwife, if we experience any sense of doubt or reluctance or uneasiness in response to their advice or behaviour, we have a moral and ethical duty to ourselves and our baby to respect and trust this intuition. As Rachel Wolfe and Sarah Fisher describe in their accounts in this issue of the journal, parents too often look back at their birth experience wishing they had trusted themselves more. Medical authority is not always right, and even when it may be right for some, it may not be right for others. Therefore, unquestioning obedience, in the presence of personal doubt, could be regarded as irresponsible - we have only to think of the Milgram experiments in the 1960s to be reminded of this.

Unquestioning obedience (“I will do anything they tell me to”) is also unfair to the practitioner who is then burdened with a sense of total responsibility. It is a powerful sense, but only a sense because, legally, nothing can happen without the mother’s consent. In truth, the practitioner is only responsible for the quality of care that they offer; they are not responsible for whether or not that care is accepted. Unfortunately, this sense of total responsibility is so real and so burdensome (as is the accompanying fear of litigation) that the practitioner, as Mary Nolan touches on in her article, may feel that they cannot trust themselves, or indeed, trust the mother. Instead, just as many parents unquestioningly trust the midwife and doctor, many midwives and doctors unquestioningly trust the current protocols and feel unsafe when parents do not comply. This is when the shroud-waving begins - further undermining the ability of parents to trust their own instincts.

Parents who do experience doubt, reluctance or uneasiness about medical advice are obliged to make an active decision. In the face of uncertainty, a common decision-making strategy is to ‘do what most other people do’, or ‘to go with the flow’. But there are two flows, the flow of the physiological process, a flow that does not require decisions, only responses, and the mainstream maternity care flow, which, in modern times, is the deeper channel carved by what most people currently do. Naturally, without one’s hand on the rudder, this is the flow that we tend to be swept into, and to resist this flow risks incurring social disapprobation. Reflecting on freebirth recently, Malika Bonapace, who writes in this issue, said to me:

Isn’t it ironic that those who place 100% of the responsibility for their birth into the hands of strangers are considered the most responsible, while those who assume 100% of the responsibility for their birth are considered the most irresponsible.

Even if we know the maternity care flow has risks or repercussions we would rather avoid, the fear of the disapproval makes it hard to really trust ourselves and our instincts. What to do?

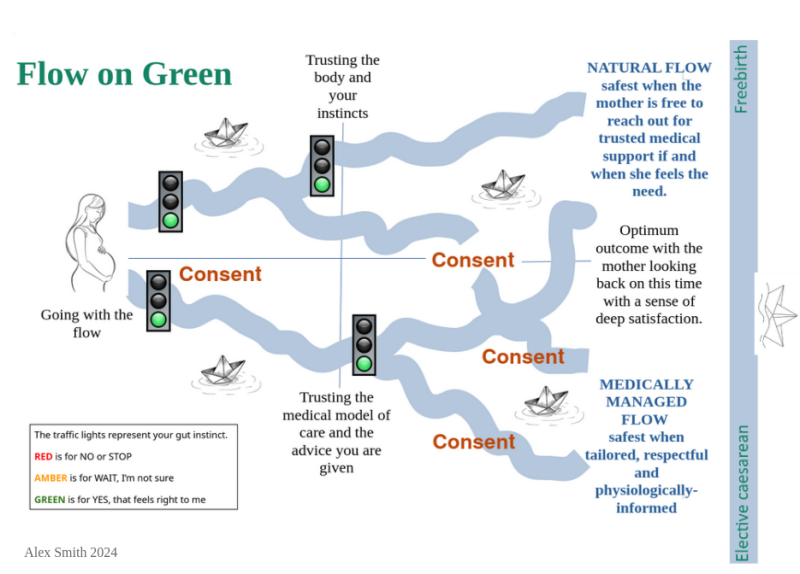

When parents tell me that they wouldn’t trust themselves to know what to do at any given point, I invite them to ‘trust their traffic lights’.

Imagine that you have an internal set of traffic lights, red, amber and green:

The red light would flash if someone wants you to agree to something that immediately makes you feel distressed, on high alert, afraid or coerced. Red is for when your instinct is to shout NO or STOP.

The green light would flash if the suggestion immediately triggers a wave of relief and a sense of being heard, cared for and respected, if it resonates comfortably with every fibre of your body and you want to shout YES, LET’S GO.

The amber light would flash if you are just not sure. You may need time alone to tune in to your body, you may need more information, you may need to discuss things in private…or you may just be feeling ‘possibly yes, but not just now’. Amber is always WAIT.

The body is intelligent and the green light will always respond to an offer of help if the situation is urgent. Reaching out for help is one of our deepest instincts. It is safe (as safe as life gets - stairs, road and toaster safe) to trust our internal traffic lights. Whichever flow you decide to go with, only flow on green.

Flowing on green means that you trust and do what feels best at any given point. The physiological process of labour is like a river. With rare exception, it is likely to flow unimpeded, to its destination. No decisions are required but instincts might draw you to move or vocalise in certain ways, seek a deep warm bath, hide away in the loo, or call out for help. The body knows what it is doing. As Kath Revell writes in this issue, “Trust is at the heart of physiological birth”, and this was certainly the case with Salli Ward when she had her three babies at home. When the idea of letting nature take her course stirs a green light feeling, trusting this is entirely reasonable and responsible, and safer today than ever before with easy access to medical support should the lights change.

The maternity care flow in labour is more like a canal with a series of ‘locks’ representing the sequence of predetermined maternity care customs and procedures that both disrupt and then govern the course of labour.1 Lock one: labour must start by a certain time or be medically induced. The mother must trust whether this is really necessary or not. Lock two: when labour starts spontaneously the mother must trust herself to know when to ‘go in’, or call the hospital and trust that someone who she has never met will be better placed to make that judgement. Lock three: when she does go in the mother is ‘triaged’ to determine whether she can go to the labour ward, her own feelings about this are not to be trusted; and so the flow proceeds.

If a mother has decided to go with the maternity care flow, each ‘lock’ (or offer of a test, examination or procedure) is a chance to check in with the traffic lights, and to only flow on green. For example:

When a mother is told she is not in labour and should go home, but she is not so sure (amber light) she can simply stay put and WAIT for a while.

If she really doesn’t want a vaginal examination but is told she has to have one in order to progress to the labour ward (red light), she can cheerfully and firmly say NO.

If she is having really strong contractions and the midwife offers to get the pool ready and the thought of that feels glorious (green light) she will say YES, LET’S GO!

Even when there is a good reason for the advice being given, there are always alternative ways of going about things. Nothing can be done without the mother’s willing consent, and legally, gaining consent must involve all the options being on the table.3 However, the maternity care flow runs along a deeply entrenched ‘canal’. The midwife or doctor’s assumption that you will ‘go with the flow’ (accepting every procedure offered) is a powerful force for compliance. It almost feels dangerous, badly behaved and ungrateful to say no, stop or wait.

If the mother’s red or amber light is flashing it may be useful for everyone to know what the possibility of actual danger really is. The parents should be able to trust the person offering the procedure to provide an accurate answer and then to support the mother’s decision. For example, a midwife offering induction because pregnancy is continuing beyond 40 weeks could refer to research showing that for mothers continuing pregnancy to 42 weeks or beyond the possibility of a perinatal death is about 2 in 1000 compared with 1.3 in 1000 for babies born at 40 weeks, and that when babies struggling to grow in the womb are taken out of the equation, there may be no difference in risk at all. She should then have the information to hand that will enable the mother to balance this risk with the risks of induction. If the parents cannot trust the midwife or doctor to offer impartial and balanced information - and if the midwife or doctor cannot trust that they will still have their job if they do support women in this way - then the system is untrustworthy. As Claire Dunn and Ryan Jones found from their separate experiences, when trust in maternity care has been breached it feels quite shocking.

The maternity care flow works best when, as midwives Marie Lewis and Bernadett Kasza note in their personal reflections, there is continuity of carer and a developed relationship of trust between the mother and her midwife. The AIMS Campaigns team actively campaigns for this, because as described in this issue, continuity matters. When there is no continuity, the next best thing is that every ‘stranger’ practitioner trusts and respects the consent process by offering every option at every ‘lock’. For example:

At this point in the pregnancy we are able to offer you induction of labour, but there are other options you may prefer to consider. What are your immediate feelings? Here is some information so that you can consider the pros and cons. Have a think and let me know. Whatever you decide, you have our total support.

Truly consensual care allows the person, the person whose body is doing the work, to trust their instincts and to flow through those ‘lock gates’ on green. At the same time it safeguards the practitioner who is acting in accordance with their code of practice4 by offering truly consensual care at every step of the way - a prerequisite of every NICE guideline and an absolute legal requirement. The midwife or doctor practising in this way need have no fear that ‘trusting the mother’ may result in disciplinary procedures, as they will be recording this “properly informed consent” process in the notes - "before carrying out any action”. No one can argue with that, it is stipulated in The Code.5 Trusting the law (the ‘rules’) in this way is a brilliant form of ‘working to rule’ or of non-violent direct action, or ironically, of civil disobedience (ironic because the act of resistance is taking the form of obedience to the law) - and perhaps even, a brilliant way of changing the system and restoring our trust in birth.

Continuing the exploration of trust in this issue, AIMS volunteer Danielle Gilmour has sourced two thought-provoking poems on the theme. Jo Dagustun reflects on whether the word ‘trust’ in relation to ‘NHS trusts’ is simply a way to seduce us into believing exactly what they want us to believe about their organisation, and Gemma McKenzie challenges yet another attempt by health care practitioners to silence women and their use of the term ‘obstetric violence’. Birth activist Mars Lord gives an impassioned account of the disparities for Black bodied women in trusting maternity care, while the AIMS Campaigns Team calls on all birth activists to help their local community - and improve national practice - by investigating the accessibility (and trustworthiness) of the Care Quality Commission (CQC)’s rating for their local maternity services. In her second piece, Jo Dagustun calls on us all to ‘actively’ attend more conferences, and Nadia Higson on behalf of the AIMS Management Team asks you to consider supporting us to continue our work by becoming an AIMS member, if you are not already one. We also have an update from our PIMS (Physiology-Informed Maternity Services) team, and last but never least, the AIMS Campaigns Team updates us about their recent activities.

We are very grateful to all the volunteers who help in the production of our Journal: our authors, peer reviewers, proofreaders, website uploaders and, of course, our readers and supporters. This edition especially benefited from the help of Anne Glover, Katherine Revell, Jo Dagustun, Jo Williams, Esther Shackleton, Carolyn Warrington, Danielle Gilmour, Salli Ward and Josey Smith.

The theme for the December issue of the AIMS journal will be focused on the experience of maternity care for Deaf parents and on the experience of parents who find that their baby is deaf. If you have an experience or insight about this topic and would like to write about it for the journal - I would love to hear from you. Please email: alex.smith@aims.org.uk

1 I once heard an obstetrician proudly describe the channelling of labouring women through the hospital care system as being like the channelling of flight passengers through the airport security system.

2 Adapted from an image in the Encyclopedia Britannica

3 AIMS Making decisions about your care. www.aims.org.uk/information/item/making-decisions

4 NMC The Code: Professional standards of practice and behaviour for nurses, midwives and nursing associates.

5 NMC The Code: “4.2 make sure that you get properly informed consent and document it before carrying out any action.”

The AIMS Journal spearheads discussions about change and development in the maternity services..

AIMS Journal articles on the website go back to 1960, offering an important historical record of maternity issues over the past 60 years. Please check the date of the article because the situation that it discusses may have changed since it was published. We are also very aware that the language used in many articles may not be the language that AIMS would use today.

To contact the editors, please email: journal@aims.org.uk

We make the AIMS Journal freely available so that as many people as possible can benefit from the articles. If you found this article interesting please consider supporting us by becoming an AIMS member or making a donation. We are a small charity that accepts no commercial sponsorship, in order to preserve our reputation for providing impartial, evidence-based information.

AIMS supports all maternity service users to navigate the system as it exists, and campaigns for a system which truly meets the needs of all.