AIMS Journal, 2024, Vol 36, No 1

Image: MBRRACE-UK

By Catharine Hart

Last year’s annual MBRRACE (Mothers and Babies: Reducing Risk through Audit and Confidential Enquiries)[1] report into maternal death in the UK was published in October 2023, reporting on the women and birthing people who died in the UK and Ireland between 2019-2021. The current system of confidential enquiries began in 1952, initially reporting on deaths every three years;[2] this is the tenth report published since MBRRACE began to report annually[2]. The story behind each woman who died is looked at in detail, so patterns can be recognised and real lessons learnt to prevent these tragic events occurring again. The full report is available here,[3] with infographic[4] and lay summary[5] versions also available.

In 2019-21, 572 women died during and up to the first year after pregnancy; 241 of these deaths occurred during pregnancy or up to six weeks after birth. This is out of 2 066 997 women giving birth in the UK and is an increase on last year’s figures, but this increase is not statistically significant and includes deaths from the COVID-19 pandemic. Thankfully, the maternal mortality rate in the UK remains low, a rate of 11.7 women per 100 000 pregnancies. However, the government’s target to reduce maternal mortality by 50% by 2025 compared to 2010 levels will likely be missed.

COVID-19, cardiac disease and blood clots were the three joint highest causes of death overall (each responsible for the deaths of 33 women). Blood clots remain the highest cause of death during pregnancy and up to 6 weeks postnatally. The death rate from obstetric haemorrhage has increased, although this is not statistically significant and deaths from eclampsia or pre-eclampsia have also now increased to nine women (a significant increase compared with five women who died from this cause in 2015-17). Seventeen women’s deaths were associated with epilepsy, including from SUDEP (Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy), an increase in recent years and nearly double the rate from 2013-15, also noted in previous MBRRACE reports.[6] The authors state that this increase is associated with changes in the guidance around prescribing epilepsy medications, which would likely have affected pregnant women. The report recommends more personalised care, including a good understanding of each woman’s individual circumstances, when discussing the benefits as well as risks of medication, for example, echoing previous recommendations from MBRRACE.[6]

|

|

Images: MBRRACE-UK

Stark racial inequalities in maternal mortality unfortunately still persist, although they are decreasing slightly. The shocking statistic that Black women in the UK were five times more likely to die during or in the year after pregnancy, compared with White women, was highlighted by MBRRACE in 2019, although racial disparities were known about before this.[6]

This report shows that Black women still remain nearly four times more likely to die (3.7), compared with White women. This is also not the only racial disparity, with Asian women also having around twice the risk, compared with White women. 25% of the women or birthing people who died were born outside of the UK (where place of birth was recorded), although the death rates for those women born in the UK was not significantly different from those born outside of the UK.

This report clearly shows stark effects of social inequalities of health, with women in the most deprived areas still around two times more likely to die. 12% of the women who died had multiple severe disadvantages recorded – especially mental health issues, domestic abuse and substance use. The authors note that this should be thought of as a “minimum” as many of these factors aren’t reported or recorded. Only 53% of the women who died received the “recommended” number of antenatal care appointments. The proportion of women who died who had involvement with social care was 21%, a figure which has increased in recent years. There was an intersection of medical and social problems, compounding the risk factors for some of the most vulnerable women, who were often disengaged from health services. The risk of disjointed working was highlighted, with failures of communication between teams. Vulnerable women were not listened to, received inappropriate care and felt exposed and scrutinised. Mental health continues to be a significant factor, with 10% of women or birthing people’s deaths directly caused by mental health related issues. Suicide remains the leading cause of death in the postnatal period, with mental health causes overall accounting for 39% of deaths in this time period. It is clear that further action is needed on mental health issues and really wholescale action to address the needs of the most vulnerable women.[7]

Concerningly, this report only takes us up to, but not into, the cost-of-living crisis, so even more widening disparities in death rates may be expected next year.[8] A shocking 89% of all the deaths occurred postnatally (an increase from last year’s figure of 86%), emphasising the need for increased resourcing for postnatal care, especially since it is already recognised as being under-resourced. [9],[10]

Deaths from direct causes have only decreased by 1% since 2010 (excluding deaths from COVID-19) and the authors state that “There was evidence of a maternity system under pressure in the care of many women who died”.[3] It is vital that all healthcare professionals are given the training and resources to be able to keep up-to-date in their practice and have the skills to care for women with complex mental, physical and social care needs. Unfortunately, there are currently restrictions being put on the authors of the report, including that all recommendations must be ‘cost neutral’. This undermines the integrity of the report and prevents the authors from making many recommendations for real change, which would require increased investment.

This latest MBRRACE-UK perinatal report[11] was published in September 2023 and presents the annual confidential enquiry into perinatal deaths (stillbirths and neonatal deaths – deaths in the first 28 days of life) for the year 2021. An infographic version is also available here..[12] Unfortunately, the overall stillbirth and the neonatal death rates both increased this year, for the first time in seven years, to 3.54 per 1000 births (compared with 3.33 in 2020) and 1.65 per 1000 live births (compared to 1.53 in 2020). The overall perinatal mortality rate was 5.19 per 1,000 total births (compared with 4.85 in 2020). These year-on-year increases are thought to be related to the “direct and indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic”.[13]

There are variations in these rates between the devolved nations, with Scotland having the lowest stillbirth rate (3.27 per 1000 births) and Northern Ireland the highest (4.09 per 1000 births). There was also quite wide variation in the rates between different individual units, even after adjusting for the type of care available (e.g. intensive care etc.). Babies born preterm (before 37 weeks) make up over 70% of both stillbirths and neonatal deaths. The cause of death remains unknown for around one third of stillborn babies.

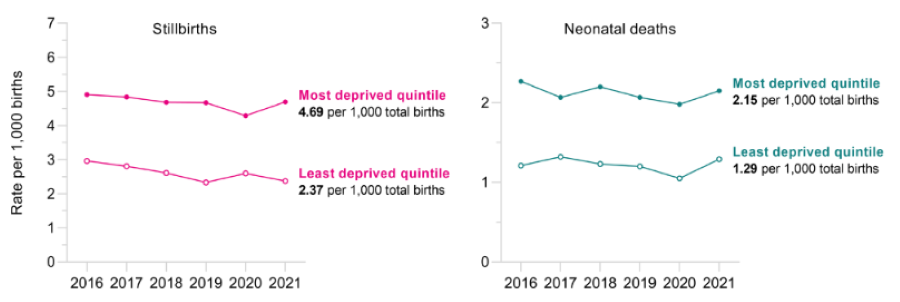

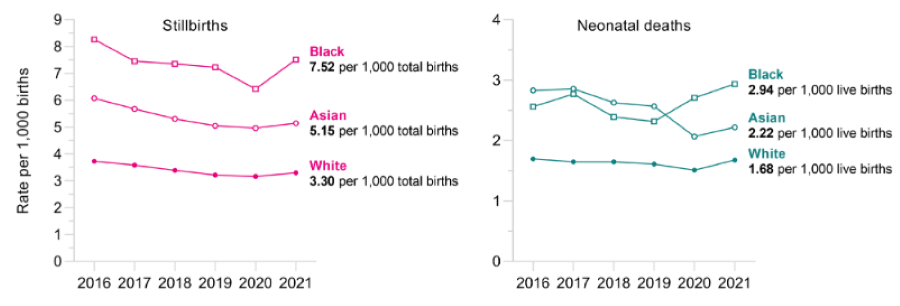

As in previous perinatal reports, large disparities in the rate of stillbirth or neonatal death remain between ethnic groups. Black babies have the highest rate of stillbirth or death in the first month of life compared to babies of all other ethnicities, with more than double the rate of stillbirth and just under double the rate of neonatal death compared with their White counterparts. Asian babies also have around 50% higher rates of both stillbirth and neonatal death. These differences increase with social deprivation.

Women in the most deprived areas have around twice the rate of stillbirth and neonatal death, compared with those from the least deprived areas. It is very concerning that inequalities along both the lines of ethnicity and socioeconomic deprivation widened in 2021, with increases in the stillbirth and neonatal death rates for babies of Black, Asian and White ethnicities and babies from the most deprived areas, as seen in the graphs below. There is currently a national target to reduce stillbirth and neonatal mortality rates by 50% by 2025, compared to 2010 levels.[13] It is clear that these disparities must be addressed urgently if there is to be any chance of meeting this target.

Images: MBRRACE-UK

The focus of these two reports was to investigate differences in the quality of care provided to Black, Asian and White women and birthing people who all sadly experienced the loss of a baby during late pregnancy (stillbirth) or a neonatal death in the year 2019. There are two separate reports – a comparison of the care of Black and White women and a comparison of the care of Asian and White women, all of whom experienced a stillbirth or neonatal death. The aim was to find out whether care guidelines were followed, if improvements in care could have prevented these outcomes and what lessons can be learned to help prevent these outcomes for Black and Asian women in the future.

These reports are based on medical records and “the women’s voice is rarely heard in the notes”.[14] The authors also acknowledge that they don’t have access to information about specific care environments or cultures, which could mean that issues such as racism at a policy or organisational level cannot always be picked up on.

This report looked at the care of 36 Black and 35 White mothers and babies. The main report is available here[15] with a lay summary[16] and infographic version[17] also available. For the year 2019, babies of Black or Black British ethnicity have a 124% increased rate of stillbirth and 43% higher rate of neonatal death, compared with White babies. Black women or babies were much more likely to have significant issues identified with their care (84%, compared to 69% of White women or babies), although the authors suggested that improvements in care might have made a difference to the outcomes of the mother or baby in similar proportions of women from both groups.

Issues found in the care given included poor record keeping, with inconsistency in the recording of ethnicity, nationality and citizenship status. Identification of language needs and interpreter provision was judged “inadequate across all ethnic groups”.[15] None of the women who required interpreters was provided with one throughout their care (this also includes the Asian women in the second report) and there was inappropriate use of family members and healthcare professionals for interpreting. Many complex social risk factors were not recorded, especially in White women.

Although some aspects of access to care and engagement (late booking, follow up of non-attendance) was similar between Black and White women, Black women were more likely to be disengaged or experience barriers to accessing some specific aspects of care. For example, oral glucose tolerance tests weren’t offered to over 20% of eligible Black women (compared with 3% of White women). None of the Black women was offered a high dose of Vitamin D as is recommended. Around 50% of all parents experienced sub-optimal neonatal care, with similar rates for Black, Asian and White parents. There were also issues around information giving, including that only 47% of Black women were documented as having been given information about reduced fetal movements, compared with 58% of White women. Some women reported not being given clear information about their care or what services were available. This led to some women stopping medication without a full discussion, disengaging with services and not attending appointments.[18]

This report looked at the care of 34 Asian and 35 White mothers and babies. The main report is here,[19], with a lay summary[20] and infographic version[21] also available. For the year 2019, babies of Asian ethnicity were at 57% increased risk of stillbirth and 59% increased risk of neonatal death, compared with White babies. The authors thought that improvements in care might have made a difference to the outcome of the baby for 26% of Asian and 49% of White women and the outcome of the mother in 59% of Asian and 69% of White women. There were similar issues found with recording ethnicity or citizenship statues and interpreter provision as in the other report although more language barriers were identified in Asian women. The report noted that Asian women were more likely to decline antenatal screening for chromosomal conditions (35%, compared to 6% of White women). There may be many reasons for this which the report doesn’t really go into. AIMS supports the recommendation to provide more information about antenatal screening tests, including translated information to overcome language barriers, as long as this is unbiased information and women are truly supported in their decisions, free from any coercion. All women have the right to accept or decline any aspect of care and this shouldn’t be seen as a “problem”, as long as any refusal is an “informed refusal”.

Fewer episodes of good care were recognised for Asian women, compared to their White counterparts and more of their care was graded poor. Oral glucose tolerance tests were again highlighted as an example of racial bias in care and were not offered to 22% of Asian women, compared with 3% of White women. There was a failure to offer the correct dose of Vitamin D to 90% of Asian women. Although fewer social risk factors were recorded for Asian women, this could also be because they were not recognised or under-recorded.[22]

This is the first confidential enquiry to take place since the national Perinatal Mortality Review Tool (PMRT)[23] was introduced in 2018. Compassionate and sensitive care at this time can help families come to terms with these devastating losses. However, unfortunately less than 10% of the reviews were graded as good quality. Problems included not enough multidisciplinary team input and the reviews not directly addressing parents’ questions or concerns. Language barriers were evident, with no parents at all who experienced language barriers being recorded as having concerns or questions about the care they had received. Most bereaved parents had appointments to review their care, but not all received a letter afterwards. Black parents were less likely to receive a letter addressed to them than White parents and complex medical language was used in these letters, despite the fact that exactly the same letter was sent to the parents as to the GP. AIMS is glad to hear that the panel recommend that women’s and families voices are now actively sought in conducting these reviews and given the chance to talk about what they have been through.

SANDS interviewed 56 Black and Asian bereaved parents for this report,[24] to learn about their experiences and what they feel needs to improve. Around half the parents felt they had received worse care or were treated differently because of their ethnicity. More than half felt that healthcare professionals didn’t listen to them; in some cases this was linked to racism or stereotyping. The report concludes that the voices of some Asian and Black parents go unheard.[22] There were examples of good, personalised care with staff advocating for those in their care. However, there was also poorly coordinated care, which led to delays and errors with serious consequences. Parents felt they weren’t always given the information about safety and risk which they needed. Some parents felt anxious when their ethnicity was highlighted as a risk factor, but this didn’t lead to enhanced care. Most bereaved parents who were involved with a review or investigation described negative experiences with complex and ineffective processes and a lack of transparency. Some parents described mistakes during reviews (e.g. incorrect paperwork) which was not only extremely upsetting but stopped them getting answers about why their baby had died.

Whilst some examples of good care were highlighted, these reports also sadly show women and families in the most distressing of situations, being treated with little empathy or kindness, unable to advocate for themselves or their babies or to give informed consent, receiving translation by untrained family members, and having a lack of control over their own decision making. They have also suffered significant barriers to care and poor care including racial discrimination and bias, which is likely to have unfortunately contributed to poor outcomes and experiences.

How can decisions be truly informed and true consent given where there are language barriers and also cultural barriers around complex medical language and procedures? Maternity services need to communicate with all women and birthing people they serve, effectively, in a format that is accessible for each person. Lack of interpretation services clearly impacts women's ability to understand their care and make informed decisions (or informed refusals!) and AIMS supports the recommendation to improve this alongside recommendations to improve recording of ethnicity, nationality and language needs and social as well as medical risk factors. All women need to be provided with unbiased, personalised information, including about the significance of their ethnicity on risk levels in a sensitive and respectful way. However, it is unclear how the recommendation to ask women about their “citizenship status” would help end racial disparities. All pregnant women in the UK are entitled to maternity care, regardless of their immigration status for example,[25] although some may be charged for care.[23] Healthcare professionals need to carry out any recommendation to ask about immigration or citizenship status sensitively, with the aim of building relationships, rather than increasing fear.

AIMS has long campaigned for equitable maternity services, where all service users receive the same levels of care, to mitigate, as far as possible, these inequalities in outcome and experiences. Yet, unfortunately, in the UK disparities along the lines of ethnicity and socioeconomic status continue. As Professor Jacqueline Dunkley-Bent (International Confederation of Midwives) urges us, the time to act is now because “every preventable death is one too many”.[26] The findings of these reports remain truly shocking. In 2021, the UK perinatal mortality rate increased for the first time in seven years and inequalities by ethnicity and deprivation have not only continued but actually increased. Although not statistically significant, we are now also seeing a rise in maternal mortality. All of the reports reviewed here urge policymakers to ensure equity for all service users, but it is clear we are a long way from this. Not only are Black and Asian mothers significantly more likely to die during or soon after pregnancy, with Black women in particular still nearly four times more likely to die, there continue to be inequalities in baby loss and baby death for Black and Asian babies too.[3] Those in the most deprived areas are still also twice as likely to die during or after pregnancy or experience a stillbirth or baby death, compared with those in the least deprived areas.

There is evidence that a caseload model of midwifery and continuity of carer might have mitigated some of these outcomes, including the rates of stillbirth and preterm birth.[27], [28] In 2019 the NHS Long Term Plan stated that 75% of women from Black, Asian and other ethnic minorities and the most deprived areas should receive continuity of carer by 2024.[29] However, this target was placed on hold in 2022 due to staffing pressures. As Jo Dagustun, our Campaigns team volunteer, has written “the cost of not making this service transformation, across a range of outcomes, is simply too high for us to accept”.[30] AIMS continues to campaign[31] for continuity of carer to be fully implemented for all, as key to a safe, personalised and equitable maternity service.

All birthing women, people and babies deserve an equal chance of survival; where ethnicity is associated with increased risks, care needs to be enhanced, along the principles of “proportionate universalism”.[32] The government must set out and fund long-term plans aimed at eliminating these inequalities in pregnancy loss and baby deaths. Specific targets with timeframes are very much needed here, as recently recommended by the House of Commons Women and Equalities committee.[33] As a first step, AIMS believes that, as a minimum, the Government must urgently implement the Women and Equalities committee recommendation to increase the annual budget for maternity services to £200–350 million, as also recommended by the Health and Social Care committee[31] and endorsed by the Ockenden report.[34]

This year’s confidential enquiry is to be welcomed as one of the first to highlight the role of caregivers and the healthcare system in contributing to these disparities. None of these reports can give us the whole answer to the question “why is this happening?”, but hopefully can add a piece to the jigsaw. Rather than just focussing on “risks inherent in Black and Brown women’s bodies”,[35] the 2023 confidential enquiry suggests other social and structural causes for these disparities instead. Unfortunately, systemic bias in the maternity services, poor practice and racial discrimination from some healthcare professionals may have contributed to the devastating outcomes and disparities discussed here. AIMS is glad to see system-wide issues being taken into account with the recommendation for the role of racism or discrimination to be explicitly considered whenever maternity policies are formulated or investigations into care are taking place. For improvements to be implemented successfully, however, there also first needs to be an enabling environment for change, with good staffing levels, knowledge and infrastructure for example. It is also clear that wide scale, transformative changes are needed across the whole maternity system to fully address these issues, including embedding anti-racism in national policies and maternity curriculums[31] and improving diversity, especially at leadership levels.[32] Black and Asian women and birthing people must be the decision makers in their own maternity care and not just be “included in the conversation” but centred in redesigning the system, to serve all equitably. AIMS continues to campaign for these changes, as outlined in our position paper on racial inequalities in maternity services,[36] alongside others working in this area, including Five X More,[37] Birthrights,[32] The Motherhood Group[38] and the All Party Parliamentary Group on Black Maternal health.[39] As Dr Christine Ekechi, consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist, says - “Let’s engage, advocate and demand change!”.[26]

Author Bio: Catharine Hart studied biology at the University of York and later trained as a midwife at the University of East Anglia. She lives with her family in Suffolk and is an AIMS volunteer and a member of the Campaigns Team.

[1] MBRRACE-UK (2024) ‘Information about MBRRACE-UK for Mothers, Parents, Families and Health Service Users’: www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/mbrrace-uk/service-users

[2] University College Cork (2024) ‘About the Confidential Maternal Death Enquiry’: www.ucc.ie/en/mde/about

[3] MBRRACE-UK (2023) ‘Saving Lives, Improving Mothers' Care State of the Nation Surveillance Report: Surveillance findings from the UK Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths 2019-21’ www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/assets/downloads/mbrrace-uk/reports/maternal-report-2023/MBRRACE-UK_Maternal_Compiled_Report_2023.pdf

[4] MBRRACE-UK (2023) ‘Key Messages from the surveillance report 2023’: www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/assets/downloads/mbrrace-uk/reports/maternal-report-2023/MBRRACE-UK_Maternal_Report_2023_-_Infographics.pdf

[5] MBRRACE-UK (2023) ‘Saving Lives Improving Mothers’ Care 2023: Lay Summary’: www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/assets/downloads/mbrrace-uk/reports/maternal-report-2023/MBRRACE-UK_Maternal_Report_2023_-_Lay_Summary.pdf

[6] Disley, M. (2021) MBRRACE report: racial inequalities in maternity outcomes continue

AIMS Journal, 33 (3): www.aims.org.uk/journal/item/mbrrace-2020-report

[7] Birthrights and Birth Companions (2019) ‘Holding it all Together’: https://hubble-live-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/birth-companions/attachment/file/276/Holding_it_all_together_-_Exec_Summary_FINAL_%2B_Action_Plan.pdf

[8] Hall, R. and Devlin, H. (2023) ‘Poverty in UK could increase death rates during or after pregnancy, warns WHO’ www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2023/jan/15/poverty-in-uk-could-increase-death-rates-during-or-after-pregnancy-warns-who

[9] Cross-Sudworth, F. et al (2024) ‘Community postnatal care delivery in England since Covid-19: A qualitative study of midwifery leaders’ perspectives and strategies’ Women and Birth, 37(1), 240-247.

[10] Royal College of Midwives and Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2020) ‘Guidance for antenatal and postnatal services in the evolving coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic’ www.rcm.org.uk/media/3837/guidance-for-antenatal-and-postnatal-services-in-the-evolving-coronavirus-pandemic-rcm-and-rcog.pdf

[11] MBRRACE-UK (2023) ‘MBRRACE-UK Perinatal Mortality Surveillance, UK Perinatal Deaths for Births from January to December 2021: State of the Nation Report’ https://timms.le.ac.uk/mbrrace-uk-perinatal-mortality/surveillance/files/MBRRACE-UK-perinatal-mortality%20surveillance-report-2021.pdf

[12] MBRRACE-UK (2023) ‘State of the Nation Report UK Perinatal Deaths for Births from January to December 2021’ https://timms.le.ac.uk/mbrrace-uk-perinatal-mortality/surveillance/files/MBRRACE-UK-perinatal-mortality%20surveillance-report-2021-infographic.pdf

[13] NHS England (2023) ‘Saving Babies’ Lives Version Three A care bundle for reducing perinatal mortality’: www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/PRN00614-Saving-babies-lives-version-three-a-care-bundle-for-reducing-perinatal-mortality.pdf

[14] MBRRACE-UK (2023) Slide presentation ‘Perinatal confidential enquiry Dec 2023 - Setting the scene’ www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/mbrrace-uk/presentations

[15] MBRRACE-UK (2023) ‘MBRRACE-UK Perinatal Confidential Enquiry, A comparison of the care of Black and White women who have experienced a stillbirth or neonatal death: State of the Nation Report’ https://timms.le.ac.uk/mbrrace-uk-perinatal-mortality/confidential-enquiries/files/MBRRACE-UK-confidential-enquiry-black-white.pdf

[16] MBRRACE-UK (2023) ‘Comparing the care of Black and White women whose babies died’ https://timms.le.ac.uk/mbrrace-uk-perinatal-mortality/confidential-enquiries/files/MBRRACE-UK-confidential%20enquiry-black-white-lay-summary.pdf

[17] MBRRACE-UK (2023) ‘Comparing the care of Black and White women whose babies died’ https://timms.le.ac.uk/mbrrace-uk-perinatal-mortality/confidential-enquiries/files/MBRRACE-UK-confidential%20enquiry-black-white-infographic.pdf

[18] Editor’s note: As noted in the following paragraph, AIMS supports people in their choices. Taking medication, attending appointments and engaging with services is optional, and non-compliance and non-engagement does not necessarily lead to poorer outcomes.

[19] MBRRACE-UK (2023) ‘MBRRACE-UK Perinatal Confidential Enquiry, A comparison of the care of Asian and White women who have experienced a stillbirth or neonatal death: State of the Nation Report’ https://timms.le.ac.uk/mbrrace-uk-perinatal-mortality/confidential-enquiries/files/MBRRACE-UK-confidential-enquiry-asian-white.pdf

[20] MBRRACE-UK (2023) ‘Comparing the care of Asian and White women whose babies died’ https://timms.le.ac.uk/mbrrace-uk-perinatal-mortality/confidential-enquiries/files/MBRRACE-UK-confidential%20enquiry-asian-white-lay-summary.pdf

[21] MBRRACE-UK (2023) ‘Comparing the care of Asian and White women whose babies died’ https://timms.le.ac.uk/mbrrace-uk-perinatal-mortality/confidential-enquiries/files/MBRRACE-UK-confidential%20enquiry-asian-white-infographic.pdf

[22] Nazmeen, B. (2023) ‘Black and Asian women’s experience of stillbirth or neonatal death: The MBRRACE-UK Perinatal Confidential Enquiry’ Maternity and Midwifery Hour, Series 12: Episode 1

" target="_blank">www.youtube.com/watch?v=7tpYAjuRHAM[23] MBRRACE (2018 - updated 2022) Perinatal Mortality Review Tool www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/mbrrace-uk/pmrt

[24] SANDS (2023) ‘The SANDS Listening Project Learning from the from the Experiences of Black and Asian Bereaved Parents’ www.sands.org.uk/sites/default/files/Sands_Listening_Project_2023.pdf

[25] Maternity Action (2022) ‘Residence rules and entitlement to NHS maternity care in England’ https://maternityaction.org.uk/advice/residence-rules-and-entitlement-to-nhs-maternity-care-in-england

[26] MBRRACE-UK (2023) Virtual Conference Presenting the MBRRACE-UK ‘Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care’ Report 2023 https://mbrrace.brightvisionevents.live/login (unfortunately this virtual conference is no longer available online)

[27] Sandall J. et al (2016) ‘Midwife‐led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women’ Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, (4). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27121907

[28] Rayment-Jones H. et al (2015) ‘An investigation of the relationship between the caseload model of midwifery for socially disadvantaged women and childbirth outcomes using routine data--a retrospective, observational study’ Midwifery 31(4): 409-17 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25661044

[29] NHS (2019) ‘The NHS Long Term Plan’ www.longtermplan.nhs.uk

[30] AIMS (2022) ‘AIMS Campaigns Update, December 2022: Continuity of Carer – challenging times, but we’re still moving forward’ www.aims.org.uk/campaigning/item/continuity-of-carer-dec-2022

[31] AIMS (2021) ‘Position Paper Continuity of Carer’: www.aims.org.uk/assets/media/726/aims-position-paper-continuity-of-carer.pdf

[32] Marmot, M. et al (2010) ‘Fair Society, Healthy Lives (The Marmot Review)’ www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review

[33] Women and Equalities Committee (2023) ‘Black Maternal Health’: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5803/cmselect/cmwomeq/94/report.html#heading-4

[34] Editor’s note: The Ockenden Report was the final report of the Independent Review of Maternity Services published in March 2022, also known as the Ockenden Review. It exposed the extensive systematic maternity failures demonstrated by Shrewsbury and Telford Hospital NHS Trust. www.gov.uk/government/publications/final-report-of-the-ockenden-review

[35] Birthrights (2022) ‘Systemic racism, not broken bodies. An inquiry into racial injustice and human rights in UK maternity care. Executive summary’ www.birthrights.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Birthrights-inquiry-systemic-racism_exec-summary_May-22-web.pdf

[36] AIMS (2022) ‘Position Paper Racial Inequalities in the Maternity Services’ www.aims.org.uk/assets/media/789/aims-position-paper-racial-inequalities-in-maternity-services.pdf

[37] Awe, T., Abe, C. R. (2020) ‘#Fivexmore: Addressing the Maternal Mortality Disparities for Black Women in the UK’ AIMS Journal, 32 (3) www.aims.org.uk/journal/item/fivexmore

[38] The Motherhood Group (2024) https://themotherhoodgroup.org

[39] Black Maternal Health APPG Official All-Party Parliamentary Group on Black Maternal Health (2024) www.instagram.com/appg_blackmaternalhealth

The AIMS Journal spearheads discussions about change and development in the maternity services..

AIMS Journal articles on the website go back to 1960, offering an important historical record of maternity issues over the past 60 years. Please check the date of the article because the situation that it discusses may have changed since it was published. We are also very aware that the language used in many articles may not be the language that AIMS would use today.

To contact the editors, please email: journal@aims.org.uk

We make the AIMS Journal freely available so that as many people as possible can benefit from the articles. If you found this article interesting please consider supporting us by becoming an AIMS member or making a donation. We are a small charity that accepts no commercial sponsorship, in order to preserve our reputation for providing impartial, evidence-based information.

AIMS supports all maternity service users to navigate the system as it exists, and campaigns for a system which truly meets the needs of all.